The International Commission on Nobility and Royalty

SOVEREIGNTY: Questions and Answers, Part 2

Books and DVDs:

Books on Monarchy Books on Royalty

Books on Royalty

Books on Nobility Books on Chivalry

Books on Chivalry

Books on Sovereignty Books on Heraldry

Books on Heraldry

Books on Genealogy Movies on Monarchy

Movies on Monarchy

Movies on Royalty Movies on Nobility

Movies on Nobility

Movies on Heraldry Movies on Genealogy

Movies on Genealogy

Preface

This article focuses on deposed monarchs --- the "de jure," internal or non-territorial sovereignty of authentic and genuine royal houses. The concepts and principles of law explained herein are not to be confused with the requirements for reigning houses that possess defacto rule although many of the fundamentals apply to both.

Each of the questions and answers below, although specific to the inquiry made, are also designed to be more or less complete in regard to the idea of how internal non-reigning sovereignty can be preserved forever or irretrievably lost. The articles as a whole add tremendous evidential weight to the legal rights and royal privileges of non-reigning royalty.

"De jure" or legal sovereignty is extremely important to the field of nobility and royalty. Without these priceless rights and entitlements, eveything is make-believe and fantasy --- nothing is real. The reason for this is that no sovereign rights means there is no "fons honorum" or right to honor, which means no authentic or genuine orders of chivalry are possible. In other words, no sovereignty means no right to use the royal prerogative, because there is no royal prerogative.

sovereignty means no right to use the royal prerogative, because there is no royal prerogative.

/browse/royal#wordorgtop) It is now generally used to describe monarchs of large territories and their close family members, but in the past, it always revolved around "the office, state or right of a king," which is sovereignty. (A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, "Royalty" & "Royalties," 1806) ". . . The nation has plainly and simply invested him with [all the glory of] sovereignty . . . invested with all the prerogatives. . . . These are called regal prerogatives, or the prerogatives of majesty." (Emerich de Vattel, The Law of Nations, Book 1, chapter 4, no. 45) Thus, a king or sovereign prince has ". . . in his own person all the rights to sovereignty and royalty. . . ." (William Rae Wilson, Esq., Travels in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Hanover, Germany, Netherlands, &c., Constitution of the Kingdom of Denmark (1826 time frame), appendix no. 16, article 6, 1826, p. 72) No one else in the kingdom has all these rights in their fullness other than the king or ruling prince. Royalty belongs only to monarchs and close family members -- not to distant relatives or offshoot lines, who are not dynasts and have no succession rights.

It is important to understand that you can have true sovereignty without royalty, as in a republic and other forms of non-royal government, but you cannot have royalty without sovereignty as it is the highest and most importance secular right on earth above all others. The subordination and dependence of royalty, or sovereign grandness, on sovereignty itself is of great importance to discern what is fake from what is genuine, true and authentic. All royal rights come from and grows out of the rights, entitlements and privileges of sovereignty. A king or sovereign prince is royal only because he holds these sovereign rights.

the highest and most importance secular right on earth above all others. The subordination and dependence of royalty, or sovereign grandness, on sovereignty itself is of great importance to discern what is fake from what is genuine, true and authentic. All royal rights come from and grows out of the rights, entitlements and privileges of sovereignty. A king or sovereign prince is royal only because he holds these sovereign rights.

The president of a republic, especially in modern times, may actually be more powerful than any king that ever lived, yet he is not a sovereign, nor does he hold any kind of regal status. A president is merely a representative of his nation or country and nothing more. Whereas, a monarch is a royal, because he is the personification of all the glory of sovereignty over the people or the land of his forefathers. This is to be the embodiment of something grand and exalted.

Thus, royal rank and status are "the [exclusive] prerogatives of sovereignty," the "emblems [or symbols] of sovereignty," and the "embodiment of sovereignty." (Webster's Third New International Dictionary, unabridged, Philip Babcock Gove, ed., "royalty," 1961, p. 1982) Sovereignty is, therefore, a central concern or core issue --- crucial to all the privileges and honors that go with it.

All of the following regal rights are inseparably connected to reigning and non-reigning sovereignty. Some of the qualities are inactive with monarchs, who are limited or deposed, but all true sovereigns hold all the following rights either in abeyance or in an active state:

(1) Jus Imperii, the right to command and legislate,

(1) Jus Imperii, the right to command and legislate,(2) Jus Gladii, the right to enforce ones commands,

(3) Jus Majestatis, the right to be honored, respected, and

(4) Jus Honorum is the right to honor and reward.

The above rights are inseparably connected as fundamental attributes of sovereignty. If legal internal sovereignty is lost or forfeited, there are no royal (grand, exalted or special) rights left. In other words, all the special qualities of royalty are lost if sovereignty is lost.

Introduction

There are many royal families on the earth, who have legally maintained their sovereign status even though they no longer are in power reigning over a territory, kingdom or principality. For example:

There are in all more than forty sovereign houses of Europe, but all do not reign over independent lands or principalities. Although many of these houses possess only the title of sovereignty and the right of royal privileges, they are equal in rank to all reigning houses, and their members intermarry freely without loss of title or rank. (George H. Merritt, "The Royal Relatives of Europe," Europe at War: a "Red Book" of the Greatest War of History, 1914, p. 132)

Europe at War: a "Red Book" of the Greatest War of History, 1914, p. 132)

In other words, deposed sovereignty is never ending, but we must add that the royal rank is maintained or lost by the rules and principles of "prescriptive" law. If the rules are not followed, royal status is irretrievably lost, which means all regal rights and privileges are forfeited. A person who has no rights cannot restore or pass on to posterity something he does not have.

Those who say that dynastic rights of deposed houses, which is de jure internal non-territorial sovereignty, cannot be lost, except by perhaps by debellatio, really have no idea what they are talking about. Sovereignty and royalty can be permanently lost in many different ways, not only for individuals and their posterity, but for whole dynasties:

A. Abdication and/or renunciation

B. Dereliction and neglect

C. Cession by treaty, will or some other arrangement

D. "Inter-vivos" transfer, sale or mortgage in ancient times

E. Tyranny, oppression or crimes against humanity

F. Papal or Imperial confiscation of all royal rights and instituting a new dynasty

G. Abandonment either overtly or by acquiescence

H. Marriage without permission

I. Unequal marriage

J. Religious Laws regarding succession

K. Prescription

L. Debellatio

M. Extinction

N. Disinheritance and exclusions

O. Consitutional stipulations and house rules

P. Designations of who or what family will or will not have direct or collateral succession rights.

Some of the above methods of loss would affect individuals and their families only, while others would impact a whole dynasty wherein the regal claim would cease to exist and they would become mere commoners with no entitlement greater than anyone else in the nation.

The point is, "The extravagant doctrines [that deposed dynastic rights can never be lost, in other words] . . . concerning the indefeasibility of hereditary claims, and the imprescriptibility of royal titles, form no part of the law of nations." Philipp Melancthon (1497-1560), "Art.18: Melancthon’s Letter to Dr. Troy, " The Annual Review, and History of Literature, vol. 4, Arthur Akin, ed., 1806, p. 263.

"Prescription," one of the above ways to forfeit a whole dynasty, which is a natural law concept in international law, is so important to the future of "de jure" nobility and non-reigning royalty, chiefly because this law is part of what governs the ". . . position and status of unlawfully dethroned Sovereign Houses." (Stephen P. Kerr, "Resolution of Monarchical Successions Under International Law," The Augustan, vol. 17, no. 4, 1975, p. 979) Prescription is a core concept of royalty and sovereignty. For example:

17, no. 4, 1975, p. 979) Prescription is a core concept of royalty and sovereignty. For example:

Dynasticism . . . [is] bound up with the principle of prescription. Indeed it might almost be said that prescription, not dynasticism, [or, in other words, prescription rather than dynastic law] provided the original rule [or key for the determination] of legitimacy. (Martin Wight, "International Legitimacy," International Relations, vol. 4, April 1972, pp. 1-28)

The rules and principles of "prescription," as juridically binding actions, are still used to determine the validity and legitimacy of "de jure" internal non-territorial sovereigns in our day and age. Much of the following "Questions and Answers" relate to both the loss and the preservation of the royal prerogative in international public law. For example, ". . . international law cannot be said to admit the imprescriptibility of sovereignty." (Eelco van Kleffens, Recueil Des Cours, Collected Courses, 1953, vol. 82, 1968, p. 86) Why? Because not only have ancient royal houses lost their internal "de jure" claims to sovereignty for centuries by this fundamental means, but modern international courts have also sustained and upheld the forfeiture or permanent loss of deposed sovereignty by the same formal rules and principles of "prescription."

fundamental means, but modern international courts have also sustained and upheld the forfeiture or permanent loss of deposed sovereignty by the same formal rules and principles of "prescription."

These important concepts need to be explained and understood. For example, to believe the idea that ". . . sovereignty formally implies a power that is absolute, perpetual, indivisible, imprescriptible and inalienable" is to believe in fairy tales or nonsense. Sovereignty may imply the above, but in real life sovereignty is not almighty, supernatural and everlasting as some want to you to believe. The truth is:

[Sovereignty] has been dividied and subdivided, acquired and lost, restricted and enlarged, times without number, and by various means, during the world's history. . . . The history of the world is full of examples of two or more nations being merged into one, and of one divided into two or more; of sovereignty lost by conquest or by voluntary surrender, and sovereignty acquired by rebellion or voluntary association. To say that a State cannot surrender or merge her own sovereignty, is to deny the existence of sovereignty itself; for how can a State be sovereign [having supreme power above all other things in life and not be able to] . . . dispose of herself? (Amos Kendall, Autobiography of Amos Kendall, William Stickney, ed., 1872, p. 597)

If sovereignty was indivisible, ". . . what became of the "indivisible" sovereignty of the British Empire when it was divided into twelve or thirteen independent States?" (Ibid., p. 596) Obviously, sovereignty is not absolute, perpetual, indivisible, imprescriptible, because it has always been limited, divisible, prescriptible and alienable. The point is:

has always been limited, divisible, prescriptible and alienable. The point is:

Indivisibility of sovereignty . . . does not belong to international law. The power of sovereigns are a bundle or collection of powers, and they may be separated one from another. (Sir Henry Maine, International Law, 1890, p. 58)

"Sovereignty is divisible, both as a matter of principle and as a matter of experience." (Ian Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law, 2008, p. 113) ". . . Defining sovereignty as inalienable, unlimited, irrevocable, and imprescriptible, ran time and again into inherently fickle dynastic practice." (Benno Teschke, The Myth of 1648, 2003, p. 228) Examples of the how dynastic sovereignty was alienable, revocable and prescriptible, etc. are myriad. Example after example exists in the history of mankind to prove this. (Ibid., pp. 228-229) Johann Wolfgang Textor, considered to be one of the late founders of international law, made it clear and unmistakable that "prescription of kingly sovereignty" is a well-known legal fact. (Synopsis of the Law of Nations, chapter 10, no. 18) How this takes place is a serious matter, because dispossessed hereditary sovereignty can be lost, and lost forever, without any recourse for recovery or renewal.

In fact, "Any right . . . [even] the right of sovereign title, may be prescribed. . ." or lost. (William Cullen Dennis, Chamizal Arbitration: Argument of the United States of America, 1911, p. 114) The point is, ". . . There is not strictly, in human nature, any such thing as an absolutely indefeasible right [that is, by definition, something incapable of being annulled or rendered void]. Sovereign right itself furnishes no exception to this general principle." (Edward Smedley and Hugh James Rose, Encyclopaedia Metropolitana; or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, vol. 2, 1845, p. 714)

absolutely indefeasible right [that is, by definition, something incapable of being annulled or rendered void]. Sovereign right itself furnishes no exception to this general principle." (Edward Smedley and Hugh James Rose, Encyclopaedia Metropolitana; or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, vol. 2, 1845, p. 714)

The point is, "[Both internal and external] sovereignty is . . . merely [a] legal conception. . . ." (Neil MacCormick, Questioning Sovereignty: Law, State, and Nation in the European Commonwealth, 1999, p. 127) Since sovereign right ". . . is conferred by law. . . ," it can also be taken away by law. (Ibid.) Dynasic or hereditary rights are:

. . . human laws . . . [that] enable men to transmit with their blood property, titles of nobility, or the hereditary right to a crown. These privileges may be forfeited for himself and his posterity. . . . They may be forfeited for posterity, because they are not natural rights. ("Problems of the Age," Catholic World, vol. 4, October 1866 to March 1867, p. 528)

They are created rights and any man-made right can be altered and changed by law, more especially by a higher law, such as, prescription, which is an integral part of the natural or higher law. These are important points in clarifying legal realities.

For example:

. . . In a [deposed] hereditary monarchy, the right to rule [which is sovereignty] remains with the royal descendant until he has lost it through the long process of prescription. (John A. Ryan, "Catholic Doctrine on the Right of Self-Government," Catholic World, vol. 108, January 1919, p. 444)

That Prescription is valid against the Claims of Sovereign Princes cannot be denied, by any who regard [or value] the Holy Scripture, Reason, [and] the practice and tranquility of the World. . . . (Charles Molley, De Jure Maritimo et Navali: or, a Treatise of Affairs Maritime and of Commerce, 1722, p. 90)

[Prescription] opposes the revival of claims from former regimes, including those of pretenders from previous dynasties, which are to be deemed [legally and lawfully] obsolete and void after the passage of a certain amount of time [50-100 years of silent abandonment]. (Frederick G. Whelan, "Time, Revolution, and Prescriptive Right in Hume's Theory of Government," Utilitas, vol. 7, no. 1, May 1995, p. 112)

. . .The revival of ancient, even [antequated and unreal] claims of sovereign rights [by deposed princes] which, on a proper view, have been lost by prescription [are to be "condemned"]. . . . (Adam Smith, Lectures on Jurisprudence, R. L. Meek, D. D. Raphael and P. G. Stein, eds., 1982, p. 37)

. . .The revival of ancient, even [antequated and unreal] claims of sovereign rights [by deposed princes] which, on a proper view, have been lost by prescription [are to be "condemned"]. . . . (Adam Smith, Lectures on Jurisprudence, R. L. Meek, D. D. Raphael and P. G. Stein, eds., 1982, p. 37)

. . . All royal rights were and are prescriptive [that is, they can be terminated]. . . . ("The Saxons in England," Hogg's Instructor, vol. 3, 1849, p. 52)

The point, dynastic rights can be lost permanently. They can also be permanently maintained and perpetuated by the most fundamental law in existence. The "Law of Nations" is nothing more or less than the "Principles of the Law of Nature applied to the Conduct and Affairs of Nations and Sovereigns." (Emerich de Vattel, full title of his book The Law of Nations) Prescription forms part of the universal, binding and "necessary" (most essential) law of all nations, rather than the "temporary," changing or "voluntary law of nations." (Hugo Grotius, The Law of Nations, "Preliminaries," no. 7-13, 21) ". . . One part of international law [is] stable and eternally the same . . . another part as shifting and changeable with the changing manners, fashions, creeds, and customs [of man]. . . ." (Sheldon Amos, The Science of Law, 1874, p. 341)

changing manners, fashions, creeds, and customs [of man]. . . ." (Sheldon Amos, The Science of Law, 1874, p. 341)

Prescription being an important part of the immoveable, enduring and changeless natural law is not just for Europe, but it is an ancient law for all ages and all people. It is immutable and eternal. Or as the Sir William Blackstone declared:

It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original." (Commentaries on the Laws of England, vol. 1, 4th ed., 1770, p. 41)

Vattel explained:

. . . As this law [natural law of which prescription is a part] is immutable, and the obligations that arise from it necessary and indispensable, nations can neither make any changes in it by their conventions, dispense with it in their own conduct, nor reciprocally release each other from the observance of it. (The Law of Nations, "Preliminaries," nos. 8-9)

The transfer of rights by prescription is a just, time-honored method, of ancient date and modern usage, for the acqusition of sovereign and royal rights. As stated by Johann Wolfgang Textor (1693-1771), a well-known international lawyer and publicist, "The modes of acquiring Kingdoms [principalities or territories] under the Law of Nations are: Election, Succession, Conquest, Alienation and Prescription." (Johann Wolfgang Textor, Synopsis of the Law of Nations, vol. 2, 1680, p. 77)

The transfer of rights by prescription is a just, time-honored method, of ancient date and modern usage, for the acqusition of sovereign and royal rights. As stated by Johann Wolfgang Textor (1693-1771), a well-known international lawyer and publicist, "The modes of acquiring Kingdoms [principalities or territories] under the Law of Nations are: Election, Succession, Conquest, Alienation and Prescription." (Johann Wolfgang Textor, Synopsis of the Law of Nations, vol. 2, 1680, p. 77)

Literally thousands of former sovereign houses have lost all their royal rights and prerogatives throughout history. These de jure rights automatically transfer from the dispossessed former rulers to the new subsequent governments by natural law. It terminates all the entitlements for the neglectful, the silent or acquiescent, and justly and ethically gives them, in their entirety, to the new possessor.

Lose of rights, however, is only one facit or aspect of prescription on both an international and domestic level. The other is, it can preserve and perpetuate deposed sovereign rights indefinitely into the future. However, certain actions are required for this. Emerich de Vattel, one of the fathers of international law, declared:

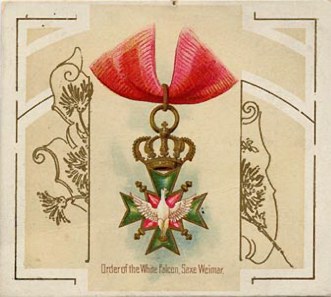

Protests answer this purpose. With sovereigns it is usual to retain the title and arms of a sovereignty or a province, as an evidence that they do not relinquish their claims to it. (Emerich de Vattel, The Law of Nations, Book 2, chapter 11, no. 145)

Others have also discussed these important rules to safeguard and protect such rights:

. . . The [actual] form of the objection [or protest] is irrelevant, so long as the dispossessed state [or exiled royal house] make clear its opposition to the acquisition of title by someone else. (Martin Dixon, Textbook on International Law, 6th ed., 2007, p. 159)

If anyone sufficiently declares by any sign that he does not wish to give up his right, even if he does not pursue it, prescription does not prevail against him. . . . If any sufficiently declares by any sign [for example, use of royal titles and symbols of sovereignty] that he does not want to give up his right, even if he does not pursue it [does not go to war over it], prescription [or loss] does not avail against him. (Christian Wolff, Jus Gentium Methodo, Scientifica Pertractatum, vol. 2, John H. Drake, trans., chapter 3, no. 361, 1934, p. 364)

If anyone sufficiently declares by any sign that he does not wish to give up his right, even if he does not pursue it, prescription does not prevail against him. . . . If any sufficiently declares by any sign [for example, use of royal titles and symbols of sovereignty] that he does not want to give up his right, even if he does not pursue it [does not go to war over it], prescription [or loss] does not avail against him. (Christian Wolff, Jus Gentium Methodo, Scientifica Pertractatum, vol. 2, John H. Drake, trans., chapter 3, no. 361, 1934, p. 364)

[In other words] one’s right is saved by protesting. Here likewise belongs the case of one who, being unwilling to give up the right of sovereignty [and royalty], claims the title and royal insignia, although [or even though] he does not possess the kingdom. (Ibid.)

[If one is] unwilling to give up the sovereignty, [he must] claim the title and royal insignia. . . . It is undoubtedly wise that the one who wishes to preserve his right, and does not wish to give it up, should give plain indications of his desire, so far as is in his power. (Christian Wolff, The Law of Nations Treated According to a Scientific Method, chapter 3, no. 364, 1974, pp. 187-188)

. . . The use of titles, shields, protests, public and solemn notifications [were all ways of interrupting prescription or maintaining internal non-territorial claims for territorially dispossessed royal houses]. (de Martins, Summary of the Modern Law of Nations of Europe, [1788] 1864 as quoted in Venezuela, Case of Venezuela in the Question of Boundary Between Venezuela and British Guiana, vol. 2, 1898, p. 295)

Some of them [the dispossessed] have retained the Titles of their pretended [that is, rightful claims to] Kingdoms and Lordships, others the Arms, and a third Sort both the Arms and Titles of those Dominions, tho' not in Possession of one Foot of Land in them. (Hugo Grotius, The Rights of War and Peace, vol. 2, Jean Barbeyrac trans., ed. & writer of notes, and Richard Tuck, ed., book 2, chapter 4, no. 1, note 5, [1625], 2005)

. . . International law states that the heads of the Houses of sovereign descent . . . retain forever the exercise of the powers attaching to them, absolutely irrespective of any territorial possession. They are protected [by law] by the continued use of their rights and titles of nobility. . . . (Monarchist World Magazine # 2, August 1955)

In other words, the head of the royal house preserves and safeguards his family’s most sacred entitlements or rights by this means.

In other words, the head of the royal house preserves and safeguards his family’s most sacred entitlements or rights by this means.Here likewise belongs the case of one who, being unwilling to give up the right of sovereignty [and royalty], claims the title and royal insignia, although [or even though] he does not possess the kingdom. (Christian Wolff, Jus Gentium Methodo, Scientifica Pertractatum, vol. 2, John H. Drake, trans., chapter 3, no. 364, 1934, p. 187) (emphasis added)

[In other words] one who, being unwilling to give up the sovereignty, [must] claim the title and royal insignia. . . . It is undoubtedly wise that the one who wishes to preserve his right, and does not wish to give it up, should give plain indications of his desire, so far as is in his power. (Ibid., pp. 187-188) (emphsis added

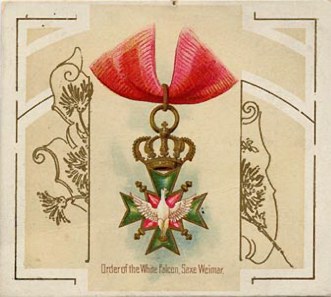

In terms of arms in heraldry, the well-known practice is to make one's claim known to all by one's coat of arms as well as by use of title and protest:

. . . Arms of Pretension are those borne by [genuine] sovereigns who have no actual authority over the states to which such arms belong, but who . . . express their prescriptive right thereunto. (Henry Gough, A Glossary of Terms used in Heraldry, 1894, p. 18)

Use of one's exalted titles and arms are central to the preservation of rights in international law as a consistent public protest to protect a claim from prescriptive legal transfer.

However, once non-territorial sovereignty is lost, all, not some, but all royal rights are lost with it. This includes the right to honor others or use the exalted titles of a sovereign. This is because such an individual is no longer royal, no longer sovereign, no longer holds the rights of supremacy, but is merely a commoner with no more authority than anyone else.

Having illustrious ancestors makes no difference. If the precious quality of sovereignty is gone or lost in any of a number of different ways listed above, so is the legitimate right to use royal titles and honor others.

One must be wary and careful and be fully informed not to be deceived by some of the charlatans or bogus princes who skillfully fight the truth and purposely blur legal realities in order to lead people astray or take advantage of innocent, unsuspecting potential victims. It is very important to understand the basic inherent facts about sovereignty and royalty, so one is not taken in by those who masquerade as authentic, but who are really only impostors, who impersonate what is real, genuine and true.

sovereignty and royalty, so one is not taken in by those who masquerade as authentic, but who are really only impostors, who impersonate what is real, genuine and true.

The following principles are based on the writings of the founders of international law as well as modern scholars and jurists. This includes treaty law, court decrees and the International Commission on Law (ICL). You will find quotes from many of the above sources throughout the following.

Click on the question or statement that interests you, but we recommend that you read each one:

(1) (Definitions)

(2) (Dynastic Law)

(3) (Legal Standing)

(4) (Court Jurisdiction)

(5) (Legality)

(6) (Dynasties can lose all Rights)

(7) (Maintaining Royal Rights)

(8) ("Prescription" Cases)

(9) ("Prescription" & Whole Nations)

(10) ("Prescription" & Legitimacy)

(11) (Monarchy & Sovereignty)

(12) (Popular Sovereignty)

(13) ("Prescription" & International Law)

(14) ("Prescription" & Tribunals)

(15) ("Prescription" & Internal Sovereignty)

(16) (Sovereign Limitations vs Independence)

(17) (Sovereign Rights vs Actual Power)

(18) (Succession Rules)

(19) (Modern Law & Ancient Rights)

(20) ("Prescription" & Cession)

(21) (Discerning Truth)

Section One: (19 Questions or Statements Answered)

(45) (Miscellaneous Questions Review)

Section Two: (Continuation of Questions and Answers)

(46) (International Law or Domestic Law?)

(47) (Vague and Uncertain?)

(48) (Dynastic & International Law)

(49) (Ancients)

(50) (Unnecessary?)

(51) (Prescription both Preserves and Destroys)

(52) (Criteria for Determining Acquiescence)

(53) (Conclusion)

Questions and Answers

(22) Some scholars have denied "prescription" in international law. If so, how can you promote it as something of such great importance to nobility and royalty?

(22) Some scholars have denied "prescription" in international law. If so, how can you promote it as something of such great importance to nobility and royalty?

In the 1800’s and early 1900’s, there were some skeptics. There probably still are. That is just the common lot of mankind to disagree. However, ". . . The idea that sovereignty is not subject to prescription has not been retained, at least not in international law. Though there are still writers [in the early 1900's] who uphold that idea, the majority rejects it." (Eelco van Kleffens, Recueil Des Cours, Collected Courses, 1953, vol. 82, 1968, p. 85) In other words, "The existence in international law of the principle of 'aquisitive prescription' for the preservation of international order and stability is acknowledged by the majority of writers." (Surya Prakash Sharma, Territorial Acquisition, Disputes, and International Law, 1997, p. 112)

One arbitration tribunal put it this way:

It is true that some later writers on the law of nations have denied that the doctrine of prescription has any place in the system of international law. But their opinion is overwhelmed by authority, at variance with practice and usage, and inconsistent with the reason of the thing. Grotins, Heineccins, Wolff, Mably, Vattel, Rutherforth, Wheaton, and Burke constitute a greatly preponderating array of authorities, both as to number and weight, upon the opposite side. (Bering Sea Tribunal of Arbitration, Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings of the Tribunal of Arbitration, no. CCLVIII, 1895, p. 45-46)

It is true that some later writers on the law of nations have denied that the doctrine of prescription has any place in the system of international law. But their opinion is overwhelmed by authority, at variance with practice and usage, and inconsistent with the reason of the thing. Grotins, Heineccins, Wolff, Mably, Vattel, Rutherforth, Wheaton, and Burke constitute a greatly preponderating array of authorities, both as to number and weight, upon the opposite side. (Bering Sea Tribunal of Arbitration, Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings of the Tribunal of Arbitration, no. CCLVIII, 1895, p. 45-46)

In discussing this subject further, they stated:

[For the same reason] which introduced this principle [the principle of prescription] into the civil jurisprudence of every country, in order to quiet possession, give security to property, stop litigation, and prevent a state of continued bad feeling and hostility between individuals, is equally powerful to introduce it, for the same purpose, into the jurisprudence which regulates the intercourse of one society with another, more especially when it is remembered that war represents between States litigation between individuals. (Ibid., p. 46)

Grotius, referring to the theory of Vasquius, that the doctrine of prescription was inapplicable as between nations, says: "yet if we admit this, there seems to follow this most unfortunate conclusion, that controversies concerning kingdoms and the boundaries of kingdoms, are never extinguished by any lapse of time; which not only tends to disturb the minds of many and perpetuate wars, but is also repugnant to the common sense of mankind." (Grotius, Be Jure Belli ac Pacis, bib. II. Cap. IV. § 1) (John Bassett Moore, A Digest of International Law, vol. 1, 1906, p. 293)

Grotius, referring to the theory of Vasquius, that the doctrine of prescription was inapplicable as between nations, says: "yet if we admit this, there seems to follow this most unfortunate conclusion, that controversies concerning kingdoms and the boundaries of kingdoms, are never extinguished by any lapse of time; which not only tends to disturb the minds of many and perpetuate wars, but is also repugnant to the common sense of mankind." (Grotius, Be Jure Belli ac Pacis, bib. II. Cap. IV. § 1) (John Bassett Moore, A Digest of International Law, vol. 1, 1906, p. 293)

In other words, ". . . international law cannot [in wisdom] be said to admit the imprescriptibility of sovereignty." (op.cit., p. 86) So we go back to the question, "Does it [prescription] exist; is it recognized by international law? Many jurists and publicists of great authority answer in the affirmative; of which number are Grotius, Vattel, Edmund Burke, Wheaton, and Phillimore." (John Norton Pomeroy, Lectures on International Law in Time of Peace, Theodore Woolsey, ed.,1886, p. 120-121) This same author then quotes Emer Vattel:

. . . Usurpation and prescription are much more necessary between sovereign states than between individuals. Their quarrels are of much greater consequence; their disputes are usually terminated only by bloody wars; and consequently the peace and happiness of mankind much more powerfully require that possession on the part of sovereigns should not be easily disturbed, — and that, if it has for a considerable length of time continued uncontested, it should be deemed just and indisputable. (Ibid., p. 121)

Not only is "prescription" essential, useful and practiced in internationally law, but ". . . the concept of prescription (which legitimizes title through the passage of time) seems to be enjoying something of a revival in the post-Cold War Era." (Cherry Bradshaw, Bloody Nations: Moral Dilemmas for Nations, States and International Relations, 2008, p. 54) In other words, it is increasingly recognized that "prescription" is a powerful ancient doctrine, which has earned worldwide respect and admiration for being just, equitable, and fair as well as being practical in not only solving domestic property problems, but for sovereignty issues for territories and whole nations.

Not only is "prescription" essential, useful and practiced in internationally law, but ". . . the concept of prescription (which legitimizes title through the passage of time) seems to be enjoying something of a revival in the post-Cold War Era." (Cherry Bradshaw, Bloody Nations: Moral Dilemmas for Nations, States and International Relations, 2008, p. 54) In other words, it is increasingly recognized that "prescription" is a powerful ancient doctrine, which has earned worldwide respect and admiration for being just, equitable, and fair as well as being practical in not only solving domestic property problems, but for sovereignty issues for territories and whole nations.

The Bering Sea Tribunal concluded that, ". . . the right of a government by prescription, based on occupancy and claim of title, to any dominion, on land or sea, of anything in the nature of property, whether corporeal, or incorporeal, [is so] . . . firmly [fixed, immovable and concluded, it is] as if the right were established by grant or as a the result of conquest or cession." (op.cit., Bering Sea Tribunal of Arbitration, p. 47) Edmund Burke declared that such surety rests:

. . . on the solid rock of prescription. The soundest, the most general, the most recognized title between man and man that is known in municipal or public jurisprudence; a title in which not arbitrary institutions, but the eternal order of things gives judgment; a title which is not the creature, but the master of positive law; a title . . . rooted in its principles in the law of nature itself, and is indeed the original ground [or fundamental understanding] of all known property. . . . (Ibid.)

In other words, "prescription" is part of the highest law of all nations. The lessor law is called the "voluntary law," which is gleaned from customs and is called "temperamentum," because it is ". . . shifting and changeable with the changing manners, fashions, creeds, and customs [of people]." (Sheldon Amos, The Science of Law, The International Scientific Series, vol. 10, 1885, p. 341) The other is the essential, fundamental moral principles called the "laws of nature," which never change and are called "summum jus." (Ibid.) Sir William Blackstone, the renown English jurist, declared the following about this greater law, which is part of the law of nations. He explained that the:

. . . law of nature [the higher law], being co-equal with mankind and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original. ("Of The Nature of Laws in General" 2009: http://libertariannation.org/a/f21l3.html)

Hugo Grotius made it clear that ". . . Prescription doth truly belong to the Law of Nature. . . ." (Samuel Pufendorf, Of the Law of Nature and Nations, Book IV, chapter 12, no. 8, p. 357) Edmund Burke also explicitly stated that "the doctrine of prescription . . . is part of the law of nature [which is part of the natural law of justice]." (Francis Canavan, "Prescriptions of Government," Edmund Burke: Appraisals and Applications, Daniel Ritchie, ed., 1990, p. 251) In other words, "prescription" in international law is considered to be a part of the stable and eternally unchanging basics, which are the foundational laws of all mankind. Time, law and practice has conferred upon the principle of "prescription" a "timeless rational validity." (Constantin Fasolt, The Limits of History, 2004, p. 115) "Prescription" is universal. "Prescription is sanctioned by a strong instinctive feeling . . . of our nature; and, in point of authority, the universal practice of mankind, in every age. . . ." (Edward Smedley and Hugh Jame Rose, Encyclopaedia Metropolitana; or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, vol. II, no. 118 "Prescription," p. 707)There is ". . . world-wide agreement as to its essential doctrines." (Charles P. Sherman, "Acquisitive Prescription: Its Existing World Uniformly," The Yale Law Journal, vol. 21, no. 2, December 1911, p. 147) In fact, without exception ". . . every civilized nation must ultimately fall back upon a prescriptive root of title [for the legitimacy and validity of their rights]." (Frederick Edwin Smith, Earl of Birkenhend, International Law, 2009, p. 63)

Hugo Grotius made it clear that ". . . Prescription doth truly belong to the Law of Nature. . . ." (Samuel Pufendorf, Of the Law of Nature and Nations, Book IV, chapter 12, no. 8, p. 357) Edmund Burke also explicitly stated that "the doctrine of prescription . . . is part of the law of nature [which is part of the natural law of justice]." (Francis Canavan, "Prescriptions of Government," Edmund Burke: Appraisals and Applications, Daniel Ritchie, ed., 1990, p. 251) In other words, "prescription" in international law is considered to be a part of the stable and eternally unchanging basics, which are the foundational laws of all mankind. Time, law and practice has conferred upon the principle of "prescription" a "timeless rational validity." (Constantin Fasolt, The Limits of History, 2004, p. 115) "Prescription" is universal. "Prescription is sanctioned by a strong instinctive feeling . . . of our nature; and, in point of authority, the universal practice of mankind, in every age. . . ." (Edward Smedley and Hugh Jame Rose, Encyclopaedia Metropolitana; or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, vol. II, no. 118 "Prescription," p. 707)There is ". . . world-wide agreement as to its essential doctrines." (Charles P. Sherman, "Acquisitive Prescription: Its Existing World Uniformly," The Yale Law Journal, vol. 21, no. 2, December 1911, p. 147) In fact, without exception ". . . every civilized nation must ultimately fall back upon a prescriptive root of title [for the legitimacy and validity of their rights]." (Frederick Edwin Smith, Earl of Birkenhend, International Law, 2009, p. 63)

. . . International Prescription, whether it be called Immemorial Possession, or by any other name [is so important that] . . . The peace of the world, the highest and best interests of humanity, the fulfillment of the ends for which States exist, require that this doctrine be firmly incorporated in the Code of International Law. (Robert Phillimore, Commentaries upon International Law, vol. 1, no. 219, 1854, p. 27)

". . . Immemorial possession . . . 'is generally recognized [as critically essential] and cannot be dispensed with.'" (Surya Prakash Sharma, Territorial Acquisition, Disputes, and International Law, 1997, p. 108) It is just that important. In fact, it is considered to be ". . . of incalculable [too great to be reckoned in] international importance." (Frederick Edwin Smith, International Law, 4th ed., revised and enlarged by James Wylie, 1911, p. 71)

"Although [long ago, not now] it [was] said [by some, not the majority] that sovereignty cannot be prescribed, [but] that [only meant] in less than a hundred years. . . ." (Jean Bodin, On Sovereignty: four chapters from the six books of the commonwealth, Julian H. Franklin, ed., 7th. ed., Book II, chapter 5, no. 608, 2004, p. 112) In other words, immemorial possession, or "immemorial prescription," was recognized as binding back then for those who neglected their rights for over 100 years. Now the loss of internal sovereignty can be lost in less than 45 years in some cases. (See "Question #33") Univerally acquiescence, implied consent or abandonment, not using royal or sovereignt titles for a royal house, etc., results in loss of all rights. "Acquienscence [is] silence or absence of protest in circumstances which generally call for . . . objection [like during usurpation]." (Ian Callum MacGibbon, "The Scope of Acquiescence in International Law," British Yearbook of International Law, vol. 31, 1954, p. 143)

[Title to territory is abandoned] by letting another country [or kingdom] assume and carry out for many years all the responsibilities and expenses in connection with [ruling] the territory concerned. Could anything be imagined more obviously amounting to [or be obviously identifying] acquiescence . . . [and] abandonment? Such a course of action, or rather inaction, disqualifies the country [or kingdom] concerned from asserting the continued existence of the title [of internal sovereignty]. (I.C. MacGibbon, "Estoppel in International Law," International and Comparative Law Quarterly, vol. 7, 1958, p. 509)

[and] abandonment? Such a course of action, or rather inaction, disqualifies the country [or kingdom] concerned from asserting the continued existence of the title [of internal sovereignty]. (I.C. MacGibbon, "Estoppel in International Law," International and Comparative Law Quarterly, vol. 7, 1958, p. 509)

That is, "prescription" is a far reaching binding juridical act in international law; and it is of enormous importance to royalty, nobility and chivalry; because it can destroy and ruin as well as preserve forever all the greatest and most important rights and regal privileges of each and every royal house. Hence, the future of nobility and royalty is at stake.

In fact, its importance can hardly be overestimated for without "prescription," nothing would be authentic, genuine or real. Consequently, no dispossessed royal house would be royal or sovereign or hold any special rights to majesty, true chivalry or nobility. All we would have is an empty void of lost memories, but no legal rights, no lingering glory, no fountain of honor and no true knight or knighthood. "Prescription" is a core principle at the very heart and soul of legitimacy --- the most important of all traits.

(See (#8) in Part I for examples of modern international usage of "prescription;" (#13) in Part I that "prescription" is a recognized and accepted principle of international law by the International Law Commission of the International Court of Justice; and (#9) in Part I is how "prescription" is applied to whole complete nations, not just small territories or border disputes)

how "prescription" is applied to whole complete nations, not just small territories or border disputes)

(23) What are the basic prescriptive principles that are so important to nobility and royalty?

(23) What are the basic prescriptive principles that are so important to nobility and royalty?

In order for acquisitive prescription to occur, the possession of the acquiring state must be:

1. á titre de souverain (consistent with sovereignty)

2. open and notorious (public) [not hidden]

3. peaceful (acquiescence by any state that has any title)

4. continuous (uninterrupted)

5. enduring (for a certain substantial length of time)

(Jessup worldwide Competition for International Law, "Bench Memorandum 2010," p. 12)

Some explanations of the above five requirements are as follows:

(1) ". . . The state [as in #1 above] must exercise authority without recognizing that another state possesses sovereignty over the area." (Brian M. Mueller, "The Falkland Islands: Will the Real Owner Please Stand Up," Notre Dame Law Review, vol. 58, rev. 616,1983, p. 7) Recognizing the sovereign rights of the dispossessed would entirely derail the "prescription" of its rights, and then by moral and ethical standards the usurper would have to restore those rights. (See "Question #41" on the right of restoration)

vol. 58, rev. 616,1983, p. 7) Recognizing the sovereign rights of the dispossessed would entirely derail the "prescription" of its rights, and then by moral and ethical standards the usurper would have to restore those rights. (See "Question #41" on the right of restoration)

(2) "Possession must be public [as in #2 above]. Because acquisitive prescription depends upon finding either express or implied acquiescence, a clandestine possession necessarily precludes acquiring title in this way." (Ibid.) Hence, rulership must be obvious, well-known and public.

(3) ". . . Peaceful possession [as in #3 above] is finding that the dispossessed state has acquiesced [abandoned overtly or by implication discarded] the possession." (Ibid.) In other words, "This meant that the possession had to go unchallenged." (Randall Lesaffer, "Argument from Roman Law in Current International Law: Occupation and Acquisitive Prescription," The European Journal of International Law, vol. 16, no. 1, 2005, p. 50) ". . . There cannot be peaceful possession unless there is an absence of objection [by the deposed monarch or government in exile]." (John O'Brien, International Law, 2001, p. 211) War, or lack of peaceful rule, does not stop "prescription." Peaceful does not refer to tranquility of rule, or a rule without problems, but to a lack of protest from the deposed former government. "'Peaceable' thus meant acquiescence by the opposing party." (Randall Lesaffer, "Argument from Roman Law in Current International Law: Occupation and Acquisitive Prescription," The European Journal of International Law, vol. 16, no.1, 2005, p. 51) One of the essential requirements for "prescription" to succeed is that there must be acquiescence, silence or lack of protest. That is what peaceful means --- uncontested or undisputed.

(4) "[As in #4 & #5 above] the possession must endure for a certain length of time." (Ibid.) This is between 40 and 100 years. (See: "Question #33" on typical time allowed for "prescription")

(4) "[As in #4 & #5 above] the possession must endure for a certain length of time." (Ibid.) This is between 40 and 100 years. (See: "Question #33" on typical time allowed for "prescription")

Some additional requirements are:

(a) "Acquisitive prescription does not operate where the acquiring state maintains possession by force." (Ibid.) That is, "prescription" cannot take place if the usurper continually has to physically fight the original sovereign to keep possession.

(b) "Diplomatic protests may . . . for a time . . . preserve the dispossessed state's claim. But if the state makes no effort to resort to other available remedies, such as referring the matter to the United Nations or the International Court of Justice, the diplomatic protests will ultimately prove ineffectual in stopping the acquisition by prescription." (Ibid.) Deposed monarchs and governments in exile, however, are not permitted to refer their cases to court as there are no tribunals that will accept such cases or that have proper jurisdiction. Therefore, in all fairness, it is determined that this requirement is not applicable to them. This would be an injustice. So consistent protest is adequate and sufficient in perpetuating their claim to the internal "de jure" right to rule. Such action legally means that the possession by the usurper was not peaceful and therefore, "prescription" cannot transfer "de jure" internal sovereignty to the usurper. (See (#4) and (#5) of Part I)

"Prescription" either transfers all the internal "de jure" rights of a former ruler and his family to the usurper or government that is presently in possession of the former ruler's territory, or it preserves and safeguards the former king's legal right to rule as long as he maintains and keeps his rights alive through the proper protest, which for a deposed royal house, as a minimum, is the use of their titles and arms. (See (#7) in Part I) For this reason, it is critical to the future o deposed royal houses that they use their titles and exercise their rights, because if they lose their sovereignty, they lose something extremely precious, unique and of great value. They would lose all their imperial and royal rights and all the regal prerogatives, honors and privileges that go with it. The point is:

the use of their titles and arms. (See (#7) in Part I) For this reason, it is critical to the future o deposed royal houses that they use their titles and exercise their rights, because if they lose their sovereignty, they lose something extremely precious, unique and of great value. They would lose all their imperial and royal rights and all the regal prerogatives, honors and privileges that go with it. The point is:

The de jure sovereignty of a state [or monarchy] which has been usurped by a foreign [or domestic] conqueror is not extinguished by such usurpation but survives as long as such sovereignty is kept alive by competent diplomatic protests. (Philip Marshall Brown, "Sovereignty in Exile," American Journal of International Law, vol. 35,1941, pp. 666-668)

Only one thing was necessary for prescription to take effect: a certain length of time --- ten, twenty, thirty or a hundred years, depending on the kind of property [sovereignty in this case] --- during which no one had challenged the rights of the possessor [or usurping government]. (Constantin Fasolt, The Limits of History, 2004, p. 113)

If this takes place:

. . . the presumption of law from undisturbed possession being, that there is no prior owner, because there is no claimant --- no better proprietary right, because there is no asserted right. The silence of other parties presumes their acquiescence: and their acquiescence presumes a defect of title on their part, or an abandonment of their title. A title once abandoned whether tacitly or expressly, cannot be resumed. (T. Twiss, The Oregon Question Examined, 1840, p. 24)

their title. A title once abandoned whether tacitly or expressly, cannot be resumed. (T. Twiss, The Oregon Question Examined, 1840, p. 24)

Royal "de jure" families must be very careful not to unwittingly throw the beautiful privileges and rights of majesty and glory away by neglect. In other words, if any "de jure" sovereign, or any of his or her heirs, do not preserve through the generations of time or make the attempt, that is, act in such a way as to preserve their rights to rule in the prescribed way, ". . . we may lawfully presume that he [or she] abandons his [or her] right. . . ." (The Law of Nations, Book II, #146) It is internationally ". . . deemed just and indisputable" if the usurper ". . . has for a considerable length of time continued [to rule the country] uncontested. . . ." (Emer de Vattel, The Law of Nations, Book II, #147) That is:

By the rules governing the principle of good faith, prolonged inaction on the part of other sovereigns [deposed monarch or government in exile] which at one time might have been in a position to contest the claims of the prescribing sovereign [the usurper] gradually comes to be viewed as acquiescence [silence or abandonment]. Such other sovereigns [deposed monarch or government in exile] are estopped [precluded or legally barred] from contesting the prescribing sovereign's title. (www.doi.gov/oia/Islandpages/acquisition_process.htm)

. . . When such silence [implied consent, neglect or abandonment] has continued for generation after generation, no explanation of it is admissible [it is legally barred]; then, lapse of time alone makes the title of the possessor absolutely indefeasible [which means "it cannot be undone, annulled, or made void"]; and adverse claims and pretensions, however strong originally, are utterly and for ever lost. (Captain F. Brinckley R.A., "The Story of the Riukiu (Loochoo) Complication," The Chrysanthemum, vol. 3, no. 3, March 1883, p. 141) (www.canequity.com/mortgage-resources/?i+D)

In other words, if no royal family consistently protested or claimed the territory, then that country or nation, to all intents and purposes, has permanently acquired all the full and complete rights to rule over the land. "Prescription" is completed "by the silence [or quietness] of the injured party [a deposed monarch] when that party is dealing with a prince [or other usurper] who possesses that which belongs to him, or sells, cedes or alienates it; silence on those occasions is equivalent to consent [or the legal and permanent abandonment of "de jure" sovereignty]." (Gabriel Bonnot de Mably quoted by Vicente Santamaría de Paredes, A Study of the Question of Boundaries between the Republics of Peru and Ecuador, Harry Weston van Dyke, trans., 1910, p. 295) "Abandonment in law, is the [implied or overt] relinquishment or renunciation of an interest, claim, privilege, possession or right, especially with the intent of never again resuming or reasserting it." (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abandonment) Abandonment means to totally and completely discard, dispense with or dump a right permanently.

At this point, the usurper's ". . . sovereignty is proved and the title acquires absolute validity." (Surya Prakash Sharma, Territorial Acquisition, Disputes, and International Law, 1997, pp. 118-119) If there was a royal house, their failure to maintain "de jure" sovereignty means they have lost everything and have became commoners, ordinary citizens, without titles, and without any rights or privileges. Once lost, sovereignty is lost forever and cannot be reclaimed. And no sovereignty means no royalty. And no royalty means no royal privileges, honors, titles, rights or prerogatives. It is a complete and total forfeiture. All that is left is the fact that one's ancestors were once sovereign and once royal.

Vattel tells us:

. . . Prescription can not be set up against an owner [a deposed sovereign] who, not being able to prosecute his right at the time [deposed monarchs and governments in exile are denied all possible ways to regain their rights], can do no more than merely give sufficient signs, in one way or another, that he [the dispossessed monarch] does not mean to abandon it. This is the purpose of protests. (Emer de Vattel, Le Droit Des Gens, Charles G. Fenwick, trans, 1758, Book II, chapter 11, no. 145, p. 158)

. . . Prescription can not be set up against an owner [a deposed sovereign] who, not being able to prosecute his right at the time [deposed monarchs and governments in exile are denied all possible ways to regain their rights], can do no more than merely give sufficient signs, in one way or another, that he [the dispossessed monarch] does not mean to abandon it. This is the purpose of protests. (Emer de Vattel, Le Droit Des Gens, Charles G. Fenwick, trans, 1758, Book II, chapter 11, no. 145, p. 158)

He then specifies the way deposed kings and sovereign princes, or their successors, can protest in a way that protects their rights. He declared, "With sovereigns the [royal or princely] title and the arms of a territory or province are retained, as an evidence that the right to it has not been abandoned." (Ibid.) In other words, to keep or maintain the "right" to rule --- the royal privilege, a "de jure" sovereign, or his or her successors, must continue to use their rightful titles, and former arms as a minimum. They could, in addition, knight or honor others in the name and authority of their former kingdom or principality, or they could create a new order of chivalry, as rightful "de jure" sovereigns, successors or heirs. All such behavior prevents the loss of sovereignty, because both deposed monarchs and governments cannot take their claims to any tribunal on earth, nor can they wage war to get their territory back again. All they have left is to use their titles and exercise them as a protest.

"Prescription" can also be contested and easily defeated by an official declaration of one's legitimate title or right to rule in a number of ways to keep the claims active, present and well-known. A good example of this is in an article on the Imperial House of Hohenzollern where is stated in no uncertain terms that, "The House of Hohenzollern never relinquished their claims to the thrones of Prussia and the German Empire." (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hohenzollern) In addition, they must of necessity continue the claim in the prescribed way in every generation, so there is no question about who has the full and complete right; and to preserve it for posterity to be enjoyed both in the present and for future generations. (See (#6) in Part I for a greater understanding of the rules of "prescription.")

and well-known. A good example of this is in an article on the Imperial House of Hohenzollern where is stated in no uncertain terms that, "The House of Hohenzollern never relinquished their claims to the thrones of Prussia and the German Empire." (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hohenzollern) In addition, they must of necessity continue the claim in the prescribed way in every generation, so there is no question about who has the full and complete right; and to preserve it for posterity to be enjoyed both in the present and for future generations. (See (#6) in Part I for a greater understanding of the rules of "prescription.")

(24) Sometimes it is confusing to understand all the ins and outs of "prescription" and the law. What are the basics of recognition, international tribunals, and their relationship to deposed monarchs? Please clarify.

(24) Sometimes it is confusing to understand all the ins and outs of "prescription" and the law. What are the basics of recognition, international tribunals, and their relationship to deposed monarchs? Please clarify.

Thank you for asking. Recognition of countries by other nations doesn't change anything internally or legally. So it does not have any bearing on the internal legal rights of deposed kings and sovereign princes, nor does it impact on the legality of governments in exile. The legitimacy or validity of "de jure" internal sovereignty is outside of the authority of a nation's right to recognize or not to recognize others countries internal affairs under international law.

Sometimes deposed monarchs and governments are recognized, but it changes nothing about the reality of their sovereignty. Recognition is a political and not a legal reality. In fact, ". . . the distinction between de facto and de jure recognition is largely discredited, and . . . if there is a distinction it does not matter legally." (John Dugard, International Law: a South African Perspective, 2008, p. 116 and Ian Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law, 6th ed., 2003, p. 91) The point is, ". . . Sovereignty is neither created by recognition nor destroyed by nonrecognition." (The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, edition 15, part 3, vol. 17, 1981, p. 312) The simple truth is that recognition is not necessary, nor does it have any important effect one way or another on the internal rights and privileges of dispossessed royal houses. (See (#5) in Part I for more information on this.)

". . . the distinction between de facto and de jure recognition is largely discredited, and . . . if there is a distinction it does not matter legally." (John Dugard, International Law: a South African Perspective, 2008, p. 116 and Ian Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law, 6th ed., 2003, p. 91) The point is, ". . . Sovereignty is neither created by recognition nor destroyed by nonrecognition." (The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, edition 15, part 3, vol. 17, 1981, p. 312) The simple truth is that recognition is not necessary, nor does it have any important effect one way or another on the internal rights and privileges of dispossessed royal houses. (See (#5) in Part I for more information on this.)

Likewise, international court or arbitration tribunals have no jurisdiction or influence on dispossessed kings and sovereign princes or their successors. Neither do they have any impact on the legitimacy of governments in exile. Such cases cannot be brought before any tribunal or court on earth. In other words, such access is completely denied to deposed monarchs. (See (#3) in Part I) However, "prescriptive" rules do provide a way to preserve their "de jure" internal rights, or to lose them irretrievably. Both the preservation and the lose is legally adjudicated or accomplished outside of any court decree or verdict by virtue of recognized juridical acts.

The following provides two good examples of "prescription" completed, without court or tribunal involvement. The first took place in the conflict surrounding the island of St. Lucia. The British took over the island in 1639, but lost it due to a native uprising in 1640. But because they failed to adequately protest the French takeover of the Island in 1650, they lost it --- especially after eighty years of acquiescence or silence when they should have protested. The island formally became the "prescriptive" sovereign possession of the kingdom of France without court involvement in 1713. (John McHugo, "How to Prove Title to Territory: a Brief, Practical Introduction to the Law and Evidence," Boundary & Territory Briefing, vol. 4, no. 2, 1998, p. 5)

protested. The island formally became the "prescriptive" sovereign possession of the kingdom of France without court involvement in 1713. (John McHugo, "How to Prove Title to Territory: a Brief, Practical Introduction to the Law and Evidence," Boundary & Territory Briefing, vol. 4, no. 2, 1998, p. 5)

The second example involves the how the Egyptian government ruled over both Egypt and the Sudan starting in 1820. After sixty-five years of peaceful rule, the Sudan was lost to the Mahdi rebels in 1885. But because ". . . Egypt had consistently maintained her claim despite the de facto loss of the territory ['her claims remain[ed] good']." (Ibid., pp. 6-7) So in spite of some serious challenges by England and France, the principles of "prescription" held their claim inviolate. No court or tribunal involvement was necessary, because international law was respected, acknowledged and upheld.

Hugo Grotius gives a few examples of "prescription" in ancient times achieved completely without any kind of court decree or verdict. He wrote:

. . . the Lacedaemonians, we are informed by Isocrates [(436-338 BC)], laid it down for a certain rule admitted among all nations, that the right to public territory as well as to private property was so firmly established by length of time, that it could not be disturbed; and upon this ground they rejected the claim of those who demanded the restoration of Messena [a stale uncontested claim of over 100 years].

claim of those who demanded the restoration of Messena [a stale uncontested claim of over 100 years].

Resting upon a right like this, Philip the Second was induced to declare to Titus Quintius, "that he would restore the dominions which he had subdued himself, but would upon no consideration give up the possessions which he had derived from his ancestors by a just and hereditary title. Sulpitius, speaking against Antiochus, proved how unjust it was in him to pretend, that because the Greek Nations in Asia had once been under the subjection of his forefathers, he had a right to revive those claims, and to reduce them again to a state of servitude. And upon this subject two historians, Tacitus and Diodorus may be referred to; the former of whom calls such obsolete pretentions, empty talking, and the latter treats them as idle tales and fables. (The Law of War and Peace, Book II, chapter 4, number 2)

In other words, stale claims of over 100 years are fantasy cake or make believe. The have no substance or validity, unless they used their exalted titles and/or protested in every generation so as to legally and ethically preserve the right. Otherwise, the claim was juridically abandoned, which means it was forfeited.

It is important to note that no real court or arbitration tribunal existed for "prescription" until the 20th Century. In other words, "prescription" was originally established in modern times to operate outside of court decrees and verdicts and did so for several hundred years. It also operated without court decrees and verdicts in ancient times as well. (See #19 in Part I for more examples) And even today, when such courts do exist for "defacto" government, (deposed monarchs and governments in exile are excluded from all such courts, only nation-states can participate), ". . . there is no requirement [in international law] to refer a dispute to international tribunals or other settlement mechanism." (Jessup worldwide Competition for International Law, "Bench Memorandum 2010," p. 12) One of the major reasons for this is "prescription" is all about the internal legal right to rule, rather than the external right. And as a practical matter, most countries do not care about the deposed "de jure" internal right to rule, if they have actual or "de facto" rule, that is, if they are actually ruling the nation. Besides, in most such cases, the usurper or "defacto" ruler is eventually officially recognized worldwide as both the "defacto" and "de jure" sovereign by other nations. In other words, even if this recognition is not legally binding, because it neither creates or destroys valid and legitimate internal sovereignty, it is all that most countries care about. (See (#14) in Part I for more information)

government, (deposed monarchs and governments in exile are excluded from all such courts, only nation-states can participate), ". . . there is no requirement [in international law] to refer a dispute to international tribunals or other settlement mechanism." (Jessup worldwide Competition for International Law, "Bench Memorandum 2010," p. 12) One of the major reasons for this is "prescription" is all about the internal legal right to rule, rather than the external right. And as a practical matter, most countries do not care about the deposed "de jure" internal right to rule, if they have actual or "de facto" rule, that is, if they are actually ruling the nation. Besides, in most such cases, the usurper or "defacto" ruler is eventually officially recognized worldwide as both the "defacto" and "de jure" sovereign by other nations. In other words, even if this recognition is not legally binding, because it neither creates or destroys valid and legitimate internal sovereignty, it is all that most countries care about. (See (#14) in Part I for more information)

Little attention is paid to "de jure" internal sovereignty of a deposed monarch or government in exile, even though ". . . when a foreign invader or local insurgents have occupied a state, its government may flee abroad and . . . operate as a government in exile with the same legal status it had before." (Ibid., p. 26) But this high status is an internal claim, not external, so it is often ignored, but is legally legitimate and valid forever as long as the protest or use of exalted royal titles and arms are used consistently in every generation without fail in such a way that it is unmistakably evident and sure that they have never acquiesced, or by implication abandoned or discarded their internal "de jure" claim.

as long as the protest or use of exalted royal titles and arms are used consistently in every generation without fail in such a way that it is unmistakably evident and sure that they have never acquiesced, or by implication abandoned or discarded their internal "de jure" claim.

"The basis [or core principle] of prescription in International Law is nothing else than general recognition [or the acceptance] of a fact. . . ." (Lassa Oppenheim, International Law: a Treatise, vol. 1, 1905, p. 294) If a ". . . territory has been under the effective control of a State and that has been uninterrupted and uncontested, for a long time, international law [and the nations that uphold it] will accept that reality [fully and completely without the need of a tribunal]." (Anthony Aust, Handbook of International Law, 2005, p. 38) When nations uphold the law, this is the accepted outcome.

Without exception, all countries hold their titles to sovereignty over their nations originally ". . . by a successful employment of force [violence], confirmed by time, [long] usage, [and then by] prescription. . . ." (John Randolph, American Politics, Thomas Valentine Cooper and Hector T. Fenton, eds., Book III, 1892, p. 20) No court declared their right, "prescription" as a "juridical act" gives binding legitimacy without formal or official decree. The point is, not one nation that has received legitimate and authentic internal sovereignty has ever done so by court involvement. All nations, on the face of the earth, that have internal genuine and true "de jure" sovereignty, have received that right by "prescription."

point is, not one nation that has received legitimate and authentic internal sovereignty has ever done so by court involvement. All nations, on the face of the earth, that have internal genuine and true "de jure" sovereignty, have received that right by "prescription."

In addition, there was no internal/external differentiation in ancient times --- all was internal sovereignty that "prescription" dealt with. It is the same today. For example, when a case of "prescription" does go before any one of the voluntary international tribunals, the contest is always about whether the State that had or still has the "de jure" internal right to rule will win or triumph over the State that has been exercising "defacto" rule over the territory. "Prescription" always involves a contest between the internal "de jure" rights of a former government and the internal and external overt "defacto" right of the current ruling power in charge. That is, the question is always who has the most valid and legitimate right to exercise internal sovereignty? That is the question and it is always the question when "prescription" is involved.

The answer is, title or ownership of "de jure" internal sovereignty ". . . will vest in the new state [the usurper's government] in the absence of protest." (op.cit., John McHugo, p. 5) "Protests are extremely important in international law." (Ibid.) So important that:

"Protests are extremely important in international law." (Ibid.) So important that:

The rule, long settled . . . is that long acquiescence [silence or lack of protest] by one State [dispossessed] in possession of a territory by another and in the exercise of sovereignty and dominion over it [by the usurper] is conclusive of the latter's title and rightful authority. That rule is . . . decisive [and final]." (John Fischer Williams, Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, vol. 3, 1925-1926, p. 114)

No protest means permanent and total forfeiture of sovereignty and the royal prerogative for a dethroned royal house or government in exile especially after 100 years of silent or implied consent. All that is left is that one has illustrious ancestors, but all royal, imperial or princely rights, and any authentic or genuine right to title, are terminated or irrevocably ended. To claim ancient internal rights for a house which by their inactions (lack of protest) from time immemorial, either through ancient or modern "prescription," is to believe in fairy tales or perpetuate a falsehood.

(25) Are there no exceptions to the loss of "de jure" internal sovereignty through "prescription?"

(25) Are there no exceptions to the loss of "de jure" internal sovereignty through "prescription?"

Hugo Grotius gave a very important one. He wrote, ". . . in order that silence may establish the presumption of abandonment of ownership, two conditions are requisite, that the silence be that of one who acts with knowledge and of his own free will. For the failure to act on the part of one who does not know is without legal effect." (On the Law of War and Peace, Book I, chapter IV, number 5) Not only is free will essential, but if there has been ignorance through deception or undue influence, duress, threat or some other unlawful means, then the presumption of silence and abandonment is null and void. In other words:

threat or some other unlawful means, then the presumption of silence and abandonment is null and void. In other words:

Presumption of neglect cannot justly exist, where the original owner has, by ignorance of his rights, or by deception, or personal fear, been prevented from claiming what he is entitled to. If he knew not that he had a right, he could not be supposed to relinquish it. And if fear or fraud induced his neglect, his mind could not have voluntarily consented. (John Penford Thomas, A Treatise of Universal Jurisprudence, chapter II, no. 13, 1829, p. 34)

Hugo Grotius made it clear that,"Contracts, or promises [in this case the promise of continued recognition as rulers] obtained by fraud, violence or undue fear [perpetrated by a government or some other unlawful force] entitle the injured party to full restitution." (www.constitution.org/gro/djbp_217.htm)

Obviously, criminal acts do not create lawful rights. But where there is an absent of any valid or legitimate excuse, all rights are lost. This loss takes place within a 50 to 100 year period or one generation of neglect. (See "Question #33")

or one generation of neglect. (See "Question #33")

International law has made it clear that sovereign prerogatives can be destroyed through the legal and lawful principles of justice and fairness, which is why these principles are so critical to the future of nobility and royalty.

Justice also demands that, ". . . all men are to restore what they are possessed of, if another is proved to be the rightful owner." (Hugo Grotius, On the Law of War and Peace, Book II, Chapter 10:1: www.constitution.org/gro/djbp_210.htm) This is why "prescription" protects lawful rights from ever dying, because justice does not condone theft or unfairness. The rights of sovereignty can continue forever if they are maintained in accordance with the principles of "prescription." The point is, ". . . The king does not forfeit the character of royalty merely by the loss of his kingdom. If he is unjustly despoiled of it by an usurper, or by rebels, he still preserves his rights. . . ." (Emerich de Vattel, The Law of Nations, Book II, chapter XII, no. 196) In other words, "The lawful monarch may be dethroned . . . [but] he continues to possess . . . the right of sovereignty [or right of royalty, which is the right to rule]." (Thomas Chalmers, Select Works, vol 5, 1855, p. 184) And this can last as long as their are rightful heirs and successors to properly maintain it down through the ages.

That is, as long as there is a competent protest against a fraudulent government by a valid former ruler, even if it is hundreds or even thousands of years later, then the principle of "prescription" remains in full force and power. In other words, "the right of prescription cannot be extended [to support] freebooters ['someone who takes spoils or plunder (as in war)']. . . . [because sovereignty, the highest right of power on earth, once given has] inalienable, immutable rights." (Phillip Marshall Brown, "Sovereignty in Exile," The American Journal of International Law, vol. 35, no. 4, October 1941, p. 667) That is, rights that never end if maintained.

"prescription" remains in full force and power. In other words, "the right of prescription cannot be extended [to support] freebooters ['someone who takes spoils or plunder (as in war)']. . . . [because sovereignty, the highest right of power on earth, once given has] inalienable, immutable rights." (Phillip Marshall Brown, "Sovereignty in Exile," The American Journal of International Law, vol. 35, no. 4, October 1941, p. 667) That is, rights that never end if maintained.

"But," as Emerich de Vattel declared, "if [a deposed monarchy or] the nation . . . does not resist the encroachments . . . if it makes no opposition to them, — if it preserves a profound silence, when it might and ought to speak, — its patient acquiescence becomes in length of time a tacit consent that legitimates the rights of the usurper." (The Law of Nations, Book I, chapter XVI, no. 199)

[Nevertheless] it must be observed, that silence, in order to shew tacit consent, ought to be voluntary. If the inferior nation proves that violence and fear prevented its giving testimonies of its opposition, nothing can be concluded from its silence, which therefore gives no right to the usurper. (Ibid.)

For example, "Nobody is ignorant how dangerous it commonly is for a weak state [or a deposed monarch] even to hint a claim to the possessions of a powerful monarch [or state]. In such a case, therefore, it is not easy to deduce from long silence a legal presumption of abandonment." (Ibid., Book II, chapter XI, no. 148)