The International Commission on Nobility and Royalty

SOVEREIGNTY: Questions and Answers, Part 3

Books and DVDs:

Books on Monarchy Books on Royalty

Books on Royalty

Books on Nobility Books on Chivalry

Books on Chivalry

Books on Sovereignty Books on Heraldry

Books on Heraldry

Books on Genealogy Movies on Monarchy

Movies on Monarchy

Movies on Royalty Movies on Nobility

Movies on Nobility

Movies on Heraldry Movies on Genealogy

Movies on Genealogy

Preface

This article focuses on deposed monarchs --- the "de jure," internal or non-territorial sovereignty of authentic and genuine royal houses. The concepts and principles of law explained herein are not to be confused with the requirements for reigning houses that possess defacto rule although many of the fundamentals apply to both.

Each of the questions and answers below, although specific to the inquiry made, are also designed to be more or less complete in regard to the idea of how internal non-reigning sovereignty can be preserved forever or irretrievably lost. The articles as a whole add tremendous evidential weight to the legal rights and royal privileges of non-reigning royalty.

"De jure" or legal sovereignty is extremely important to the field of nobility and royalty. Without these priceless rights and entitlements, eveything is make-believe and fantasy --- nothing is real. The reason for this is that no sovereign rights means there is no "fons honorum" or right to honor, which means no authentic or genuine orders of chivalry are possible. In other words, no sovereignty means no right to use the royal prerogative, because there is no royal prerogative.

honor, which means no authentic or genuine orders of chivalry are possible. In other words, no sovereignty means no right to use the royal prerogative, because there is no royal prerogative.

/browse/royal#wordorgtop) It is now generally used to describe monarchs of large territories and their close family members, but in the past, it always revolved around "the office, state or right of a king," which is sovereignty. (A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, "Royalty" & "Royalties," 1806) ". . . The nation has plainly and simply invested him with [all the glory of] sovereignty . . . invested with all the prerogatives. . . . These are called regal prerogatives, or the prerogatives of majesty." (Emerich de Vattel, The Law of Nations, Book 1, chapter 4, no. 45) Thus, a king or sovereign prince has ". . . in his own person all the rights to sovereignty and royalty. . . ." (William Rae Wilson, Esq., Travels in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Hanover, Germany, Netherlands, &c., Constitution of the Kingdom of Denmark (1826 time frame), appendix no. 16, article 6, 1826, p. 72) No one else in the kingdom has all these rights in their fullness other than the king or ruling prince. Royalty belongs only to monarchs and close family members -- not to distant relatives or offshoot lines, who are not dynasts and have no succession rights.

It is important to understand that you can have true sovereignty without royalty, as in a republic and other forms of non-royal government, but you cannot have royalty without sovereignty as it is the highest and most importance secular right on earth above all others. The subordination and dependence of royalty, or sovereign grandness, on sovereignty itself is of great importance to discern what is fake from what is genuine, true and authentic. All royal rights come from and grows out of the rights, entitlements and privileges of sovereignty. A king or sovereign prince is royal only because he holds these sovereign rights.

the highest and most importance secular right on earth above all others. The subordination and dependence of royalty, or sovereign grandness, on sovereignty itself is of great importance to discern what is fake from what is genuine, true and authentic. All royal rights come from and grows out of the rights, entitlements and privileges of sovereignty. A king or sovereign prince is royal only because he holds these sovereign rights.

The president of a republic, especially in modern times, may actually be more powerful than any king that ever lived, yet he is not a sovereign, nor does he hold any kind of regal status. A president is merely a representative of his nation or country and nothing more. Whereas, a monarch is a royal, because he is the personification of all the glory of sovereignty over the people or the land of his forefathers. This is to be the embodiment of something grand and exalted.

Thus, royal rank and status are "the [exclusive] prerogatives of sovereignty," the "emblems [or symbols] of sovereignty," and the "embodiment of sovereignty." (Webster's Third New International Dictionary, unabridged, Philip Babcock Gove, ed., "royalty," 1961, p. 1982) Sovereignty is, therefore, a central concern or core issue --- crucial to all the privileges and honors that go with it.

All of the following regal rights are inseparably connected to reigning and non-reigning sovereignty. Some of the qualities are inactive with monarchs, who are limited or deposed, but all true sovereigns hold all the following rights either in abeyance or in an active state:

(1) Jus Imperii, the right to command and legislate,

(1) Jus Imperii, the right to command and legislate,(2) Jus Gladii, the right to enforce ones commands,

(3) Jus Majestatis, the right to be honored, respected, and

(4) Jus Honorum is the right to honor and reward.

The above rights are inseparably connected as fundamental attributes of sovereignty. If legal internal sovereignty is lost or forfeited, there are no royal (grand, exalted or special) rights left. In other words, all the special qualities of royalty are lost if sovereignty is lost.

Introduction

There are many royal families on the earth, who have legally maintained their sovereign status even though they no longer are in power reigning over a territory, kingdom or principality. For example:

There are in all more than forty sovereign houses of Europe, but all do not reign over independent lands or principalities. Although many of these houses possess only the title of sovereignty and the right of royal privileges, they are equal in rank to all reigning houses, and their members intermarry freely without loss of title or rank. (George H. Merritt, "The Royal Relatives of Europe," Europe at War: a "Red Book" of the Greatest War of History, 1914, p. 132)

Europe at War: a "Red Book" of the Greatest War of History, 1914, p. 132)

In other words, deposed sovereignty is never ending, but we must add that the royal rank is maintained or lost by the rules and principles of "prescriptive" law. If the rules are not followed, royal status is irretrievably lost, which means all regal rights and privileges are forfeited. A person who has no rights cannot restore or pass on to posterity something he does not have.

Those who say that dynastic rights of deposed houses, which is de jure internal non-territorial sovereignty, cannot be lost, except by perhaps by debellatio, really have no idea what they are talking about. Sovereignty and royalty can be permanently lost in many different ways, not only for individuals and their posterity, but for whole dynasties:

A. Abdication and/or renunciation

B. Dereliction and neglect

C. Cession by treaty, will or some other arrangement

D. "Inter-vivos" transfer, sale or mortgage in ancient times

E. Tyranny, oppression or crimes against humanity

F. Papal or Imperial confiscation of all royal rights and instituting a new dynasty

G. Abandonment either overtly or by acquiescence

H. Marriage without permission

I. Unequal marriage

J. Religious Laws regarding succession

K. Prescription

L. Debellatio

M. Extinction

N. Disinheritance and exclusions

O. Consitutional stipulations and house rules

P. Designations of who or what family will or will not have direct or collateral succession rights.

Some of the above methods of loss would affect individuals and their families only, while others would impact a whole dynasty wherein the regal claim would cease to exist and they would become mere commoners with no entitlement greater than anyone else in the nation.

The point is, "The extravagant doctrines [that deposed dynastic rights can never be lost, in other words] . . . concerning the indefeasibility of hereditary claims, and the imprescriptibility of royal titles, form no part of the law of nations." Philipp Melancthon (1497-1560), "Art.18: Melancthon’s Letter to Dr. Troy, " The Annual Review, and History of Literature, vol. 4, Arthur Akin, ed., 1806, p. 263.

"Prescription," one of the above ways to forfeit a whole dynasty, which is a natural law concept in international law, is so important to the future of "de jure" nobility and non-reigning royalty, chiefly because this law is part of what governs the ". . . position and status of unlawfully dethroned Sovereign Houses." (Stephen P. Kerr, "Resolution of Monarchical Successions Under International Law," The Augustan, vol. 17, no. 4, 1975, p. 979) Prescription is a core concept of royalty and sovereignty. For example:

"Resolution of Monarchical Successions Under International Law," The Augustan, vol. 17, no. 4, 1975, p. 979) Prescription is a core concept of royalty and sovereignty. For example:

Dynasticism . . . [is] bound up with the principle of prescription. Indeed it might almost be said that prescription, not dynasticism, [or, in other words, prescription rather than dynastic law] provided the original rule [or key for the determination] of legitimacy." (Martin Wight, "International Legitimacy," International Relations, vol. 4, April 1972, pp. 1-28)

The rules and principles of "prescription," as juridically binding actions, are still used to determine the validity and legitimacy of "de jure" internal non-territorial sovereigns in our day and age. Much of the following "Questions and Answers" relate to both the loss and the preservation of the royal prerogative in international public law. For example, ". . . international law cannot be said to admit the imprescriptibility of sovereignty." (Eelco van Kleffens, Recueil Des Cours, Collected Courses, 1953, vol. 82, 1968, p. 86) Why? Because not only have ancient royal houses lost their internal "de jure" claims to sovereignty for centuries by this fundamental means, but modern international courts have also sustained and upheld the forfeiture or permanent loss of deposed sovereignty by the same formal rules and principles of "prescription."

fundamental means, but modern international courts have also sustained and upheld the forfeiture or permanent loss of deposed sovereignty by the same formal rules and principles of "prescription."

These important concepts need to be explained and understood. For example, to believe the idea that ". . . sovereignty formally implies a power that is absolute, perpetual, indivisible, imprescriptible and inalienable" is to believe in fairy tales or nonsense. Sovereignty may imply the above, but in real life sovereignty is not almighty, supernatural and everlasting as some want to you to believe. The truth is:

[Sovereignty] has been dividied and subdivided, acquired and lost, restricted and enlarged, times without number, and by various means, during the world's history. . . . The history of the world is full of examples of two or more nations being merged into one, and of one divided into two or more; of sovereignty lost by conquest or by voluntary surrender, and sovereignty acquired by rebellion or voluntary association. To say that a State cannot surrender or merge her own sovereignty, is to deny the existence of sovereignty itself; for how can a State be sovereign [having supreme power above all other things in life and not be able to] . . . dispose of herself? (Amos Kendall, Autobiography of Amos Kendall, William Stickney, ed., 1872, p. 597)

If sovereignty was indivisible, ". . . what became of the "indivisible" sovereignty of the British Empire when it was divided into twelve or thirteen independent States?" (Ibid., p. 596) Obviously, sovereignty is not absolute, perpetual, indivisible, imprescriptible, because it has always been limited, divisible, prescriptible and alienable. The point is:

Indivisibility of sovereignty . . . does not belong to international law. The power of sovereigns are a bundle or collection of powers, and they may be separated one from another. (Sir Henry Maine, International Law, 1890, p. 58)

"Sovereignty is divisible, both as a matter of principle and as a matter of experience." (Ian Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law, 2008, p. 113) ". . . Defining sovereignty as inalienable, unlimited, irrevocable, and imprescriptible, ran time and again into inherently fickle dynastic practice." (Benno Teschke, The Myth of 1648, 2003, p. 228) Examples of the how dynastic sovereignty was alienable, revocable and prescriptible, etc. are myriad. Example after example exists in the history of mankind to prove this. (Ibid., pp. 228-229) Johann Wolfgang Textor, considered to be one of the late founders of international law, made it clear and unmistakable that "prescription of kingly sovereignty" is a well-known legal fact. (Synopsis of the Law of Nations, chapter 10, no. 18) How this takes place is a serious matter, because dispossessed hereditary sovereignty can be lost, and lost forever, without any recourse for recovery or renewal.

fact. (Synopsis of the Law of Nations, chapter 10, no. 18) How this takes place is a serious matter, because dispossessed hereditary sovereignty can be lost, and lost forever, without any recourse for recovery or renewal.

In fact, "Any right . . . [even] the right of sovereign title, may be prescribed. . ." or lost. (William Cullen Dennis, Chamizal Arbitration: Argument of the United States of America, 1911, p. 114) The point is, ". . . There is not strictly, in human nature, any such thing as an absolutely indefeasible right [that is, by definition, something incapable of being annulled or rendered void]. Sovereign right itself furnishes no exception to this general principle." (Edward Smedley and Hugh James Rose, Encyclopaedia Metropolitana; or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, vol. 2, 1845, p. 714)

The point is, "[Both internal and external] sovereignty is . . . merely [a] legal conception. . . ." (Neil MacCormick, Questioning Sovereignty: Law, State, and Nation in the European Commonwealth, 1999, p. 127) Since sovereign right ". . . is conferred by law. . . ," it can also be taken away by law. (Ibid.) Dynasic or hereditary rights are:

. . . human laws . . . [that] enable men to transmit with their blood property, titles of nobility, or the hereditary right to a crown. These privileges may be forfeited for himself and his posterity. . . . They may be forfeited for posterity, because they are not natural rights. ("Problems of the Age," Catholic World, vol. 4, October 1866 to March 1867, p. 528)

They are created rights and any man-made right can be altered and changed by law, more especially by a higher law, such as, prescription, which is an integral part of the natural or higher law. These are important points in clarifying legal realities.

For example:

. . . In a [deposed] hereditary monarchy, the right to rule [which is sovereignty] remains with the royal descendant until he has lost it through the long process of prescription. (John A. Ryan, "Catholic Doctrine on the Right of Self-Government," Catholic World, vol. 108, January 1919, p. 444)

That Prescription is valid against the Claims of Sovereign Princes cannot be denied, by any who regard [or value] the Holy Scripture, Reason, [and] the practice and tranquility of the World. . . . (Charles Molley, De Jure Maritimo et Navali: or, a Treatise of Affairs Maritime and of Commerce, 1722, p. 90)

[Prescription] opposes the revival of claims from former regimes, including those of pretenders from previous dynasties, which are to be deemed [legally and lawfully] obsolete and void after the passage of a certain amount of time [50-100 years of silent abandonment]. (Frederick G. Whelan, "Time, Revolution, and Prescriptive Right in Hume's Theory of Government," Utilitas, vol. 7, no. 1, May 1995, p. 112)

[Prescription] opposes the revival of claims from former regimes, including those of pretenders from previous dynasties, which are to be deemed [legally and lawfully] obsolete and void after the passage of a certain amount of time [50-100 years of silent abandonment]. (Frederick G. Whelan, "Time, Revolution, and Prescriptive Right in Hume's Theory of Government," Utilitas, vol. 7, no. 1, May 1995, p. 112)

. . .The revival of ancient, even [antequated and unreal] claims of sovereign rights [by deposed princes] which, on a proper view, have been lost by prescription [are to be "condemned"]. . . . (Adam Smith, Lectures on Jurisprudence, R. L. Meek, D. D. Raphael and P. G. Stein, eds., 1982, p. 37)

. . . All royal rights were and are prescriptive [that is, they can be terminated]. . . . ("The Saxons in England," Hogg's Instructor, vol. 3, 1849, p. 52)

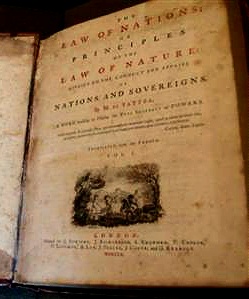

The point, dynastic rights can be lost permanently. They can also be permanently maintained and perpetuated by the most fundamental law in existence. The "Law of Nations" is nothing more or less than the "Principles of the Law of Nature applied to the Conduct and Affairs of Nations and Sovereigns." (Emerich de Vattel, full title of his book The Law of Nations) Prescription forms part of the universal, binding and "necessary" (most essential) law of all nations, rather than the "temporary," changing or "voluntary law of nations." (Hugo Grotius, The Law of Nations, "Preliminaries," no. 7-13, 21) ". . . One part of international law [is] stable and eternally the same . . . another part as shifting and changeable with the changing manners, fashions, creeds, and customs [of man]. . . ." (Sheldon Amos, The Science of Law, 1874, p. 341)

changing manners, fashions, creeds, and customs [of man]. . . ." (Sheldon Amos, The Science of Law, 1874, p. 341)

Prescription being an important part of the immoveable, enduring and changeless natural law is not just for Europe, but it is an ancient law for all ages and all people. It is immutable and eternal. Or as the Sir William Blackstone declared:

It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original." (Commentaries on the Laws of England, vol. 1, 4th ed., 1770, p. 41)

Vattel explained:

. . . As this law [natural law of which prescription is a part] is immutable, and the obligations that arise from it necessary and indispensable, nations can neither make any changes in it by their conventions, dispense with it in their own conduct, nor reciprocally release each other from the observance of it. (The Law of Nations, "Preliminaries," nos. 8-9)

The transfer of rights by prescription is a just, time-honored method, of ancient date and modern usage, for the acqusition of sovereign and royal rights. As stated by Johann Wolfgang Textor (1693-1771), a well-known international lawyer and publicist, "The modes of acquiring Kingdoms [principalities or territories] under the Law of Nations are: Election, Succession, Conquest, Alienation and Prescription." (Johann Wolfgang Textor, Synopsis of the Law of Nations, vol. 2, 1680, p. 77)

The transfer of rights by prescription is a just, time-honored method, of ancient date and modern usage, for the acqusition of sovereign and royal rights. As stated by Johann Wolfgang Textor (1693-1771), a well-known international lawyer and publicist, "The modes of acquiring Kingdoms [principalities or territories] under the Law of Nations are: Election, Succession, Conquest, Alienation and Prescription." (Johann Wolfgang Textor, Synopsis of the Law of Nations, vol. 2, 1680, p. 77)

Literally thousands of former sovereign houses have lost all their royal rights and prerogatives throughout history. These de jure rights automatically transfer from the dispossessed former rulers to the new subsequent governments by natural law. It terminates all the entitlements for the neglectful, the silent or acquiescent, and justly and ethically gives them, in their entirety, to the new possessor.

Lose of rights, however, is only one facit or aspect of prescription on both an international and domestic level. The other is, it can preserve and perpetuate deposed sovereign rights indefinitely into the future. However, certain actions are required for this. Emerich de Vattel, one of the fathers of international law, declared:

Protests answer this purpose. With sovereigns it is usual to retain the title and arms of a sovereignty or a province, as an evidence that they do not relinquish their claims to it. (Emerich de Vattel, The Law of Nations, Book 2, chapter 11, no. 145)

Others have also discussed these important rules to safeguard and protect such rights:

. . . The [actual] form of the objection [or protest] is irrelevant, so long as the dispossessed state [or exiled royal house] make clear its opposition to the acquisition of title by someone else. (Martin Dixon, Textbook on International Law, 6th ed., 2007, p. 159)

If anyone sufficiently declares by any sign that he does not wish to give up his right, even if he does not pursue it, prescription does not prevail against him. . . . If any sufficiently declares by any sign [for example, use of royal titles and symbols of sovereignty] that he does not want to give up his right, even if he does not pursue it [does not go to war over it], prescription [or loss] does not avail against him. (Christian Wolff, Jus Gentium Methodo, Scientifica Pertractatum, vol. 2, John H. Drake, trans., chapter 3, no. 361, 1934, p. 364)

If anyone sufficiently declares by any sign that he does not wish to give up his right, even if he does not pursue it, prescription does not prevail against him. . . . If any sufficiently declares by any sign [for example, use of royal titles and symbols of sovereignty] that he does not want to give up his right, even if he does not pursue it [does not go to war over it], prescription [or loss] does not avail against him. (Christian Wolff, Jus Gentium Methodo, Scientifica Pertractatum, vol. 2, John H. Drake, trans., chapter 3, no. 361, 1934, p. 364)

[In other words] one’s right is saved by protesting. Here likewise belongs the case of one who, being unwilling to give up the right of sovereignty [and royalty], claims the title and royal insignia, although [or even though] he does not possess the kingdom. (Ibid.)

[If one is] unwilling to give up the sovereignty, [he must] claim the title and royal insignia. . . . It is undoubtedly wise that the one who wishes to preserve his right, and does not wish to give it up, should give plain indications of his desire, so far as is in his power. (Christian Wolff, The Law of Nations Treated According to a Scientific Method, chapter 3, no. 364, 1974, pp. 187-188)

. . . The use of titles, shields, protests, public and solemn notifications [were all ways of interrupting prescription or maintaining internal non-territorial claims for territorially dispossessed royal houses]. (de Martins, Summary of the Modern Law of Nations of Europe, [1788] 1864 as quoted in Venezuela, Case of Venezuela in the Question of Boundary Between Venezuela and British Guiana, vol. 2, 1898, p. 295)

Some of them [the dispossessed] have retained the Titles of their pretended [that is, rightful claims to] Kingdoms and Lordships, others the Arms, and a third Sort both the Arms and Titles of those Dominions, tho' not in Possession of one Foot of Land in them. (Hugo Grotius, The Rights of War and Peace, vol. 2, Jean Barbeyrac trans., ed. & writer of notes, and Richard Tuck, ed., book 2, chapter 4, no. 1, note 5, [1625], 2005)

. . . International law states that the heads of the Houses of sovereign descent . . . retain forever the exercise of the powers attaching to them, absolutely irrespective of any territorial possession. They are protected [by law] by the continued use of their rights and titles of nobility. . . . (Monarchist World Magazine # 2, August 1955)

In other words, the head of the royal house preserves and safeguards his family’s most sacred entitlements or rights by this means.

In other words, the head of the royal house preserves and safeguards his family’s most sacred entitlements or rights by this means.Here likewise belongs the case of one who, being unwilling to give up the right of sovereignty [and royalty], claims the title and royal insignia, although [or even though] he does not possess the kingdom. (Christian Wolff, Jus Gentium Methodo, Scientifica Pertractatum, vol. 2, John H. Drake, trans., chapter 3, no. 364, 1934, p. 187) (emphasis added)

[In other words] one who, being unwilling to give up the sovereignty, [must] claim the title and royal insignia. . . . It is undoubtedly wise that the one who wishes to preserve his right, and does not wish to give it up, should give plain indications of his desire, so far as is in his power. (Ibid., pp. 187-188) (emphsis added

In terms of arms in heraldry, the well-known practice is to make one's claim known to all by one's coat of arms as well as by use of title and protest:

. . . Arms of Pretension are those borne by [genuine] sovereigns who have no actual authority over the states to which such arms belong, but who . . . express their prescriptive right thereunto. (Henry Gough, A Glossary of Terms used in Heraldry, 1894, p. 18)

Use of one's exalted titles and arms are central to the preservation of rights in international law as a consistent public protest to protect a claim from prescriptive legal transfer.

However, once non-territorial sovereignty is lost, all, not some, but all royal rights are lost with it. This includes the right to honor others or use the exalted titles of a sovereign. This is because such an individual is no longer royal, no longer sovereign, no longer holds the rights of supremacy, but is merely a commoner with no more authority than anyone else.

Having illustrious ancestors makes no difference. If the precious quality of sovereignty is gone or lost in any of a number of different ways listed above, so is the legitimate right to use royal titles and honor others.

One must be wary and careful and be fully informed not to be deceived by some of the charlatans or bogus princes who skillfully fight the truth and purposely blur legal realities in order to lead people astray or take advantage of innocent, unsuspecting potential victims. It is very important to understand the basic inherent facts about sovereignty and royalty, so one is not taken in by those who masquerade as authentic, but who are really only impostors, who impersonate what is real, genuine and true.

sovereignty and royalty, so one is not taken in by those who masquerade as authentic, but who are really only impostors, who impersonate what is real, genuine and true.

The following principles are based on the writings of the founders of international law as well as modern scholars and jurists. This includes treaty law, court decrees and the International Commission on Law (ICL). You will find quotes from many of the above sources throughout the following review.

We received a number of questions from one individual. His questions appeared to be sincere and were worthwhile to enlarge one's understanding of nobility and royalty and its future. He wrote, "Please answer the following objections to 'prescription' I found on the internet. I have a lot of questions. It is important to me." No all of his questions have been answered here as they were not all relevant or important, but the ones chosen and listed below are worth reading as they provide information on a great subject of great interest and importantce to us.

SECTION ONE:

Since most of these questions are answered either in Part I or Part II of "Sovereignty: Questions and Answer," answers will be very brief and use referrals to answers already provided. However, new proofs and new evidence have been added to confirm important truth.

SECTION TWO:

Questions and Answers

Section One:

(a) Isn't it true that in international law, if a claim is never surrendered, it lasts forever?

(a) Isn't it true that in international law, if a claim is never surrendered, it lasts forever?

No, international law is legally binding whether nations, or a deposed monarch, or his successors, want to obey it or not. (The deposed may continue to argue, but legally they don't have a leg to stand on. Legal "juridical" abandonment, whether overt or implied, is permanent forfeiture.)

(b) Isn't a "prescriptive" dispute pending forever, if no tribunal or arbitration court solves the problem?

(b) Isn't a "prescriptive" dispute pending forever, if no tribunal or arbitration court solves the problem?

No, "prescription" was created, or re-established, in the 17th Century when no international courts existed. In fact, it operated from at least 1,000 BC. "Prescription" is a "juridical act" which is legally binding outside of court. It has always has been that way for thousands of years. (See number fourteen (#14) in Part I, "Is court or arbitration necessary to effect the loss of sovereign rights for a deposed monarch?"

(c) I read that there is not even one single case that international law has ever decided over a deposed monarch.

(c) I read that there is not even one single case that international law has ever decided over a deposed monarch.

Actually, the opposite is true. Keep in mind that, ". . . In some degree every civilized nation must ultimately fall back upon a prescriptive root [or beginning] of title." (Frederick Edwin Smith, Earl of Birkenhead, International Law, 2009, p. 63) In fact, Edmund Burke made it even more inclusive, he said, ". . . All titles terminate [or end] in Prescription. . . ." (Edmund Burke, Works of Edmund Burke, vol. 9, p. 449, 2005, p. 450) In other words, "prescription" or the permanent loss of dynastic rights was a very common occurrence as it happened hundreds and hundreds of times over and over again throughout history. The point is, ". . . Title to the exercise of the royal power [or any other kind of sovereignty] arises only by prescription." (Edwin Robert Anderson Seligman and Alvin Saunders Johnson, Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, vol. 14, 1957, p. 429) 99% of all countries hold their titles to sovereign majesty over their nations originally ". . . by a successful employment of force [that is, by violence], confirmed by time, [long] usage, [and then by] prescription. . . ." (John Randolph, American Politics, Thomas Valentine Cooper and Hector T. Fenton, eds., Book III, 1892, p. 20) Literally hundreds of monarchs were deposed or dispossessed through these principles. And no court declared the right of the new nations. "Prescription" as a "juridical act" gives legitimacy without formal or official decree from a court or tribunal.

Actually, the opposite is true. Keep in mind that, ". . . In some degree every civilized nation must ultimately fall back upon a prescriptive root [or beginning] of title." (Frederick Edwin Smith, Earl of Birkenhead, International Law, 2009, p. 63) In fact, Edmund Burke made it even more inclusive, he said, ". . . All titles terminate [or end] in Prescription. . . ." (Edmund Burke, Works of Edmund Burke, vol. 9, p. 449, 2005, p. 450) In other words, "prescription" or the permanent loss of dynastic rights was a very common occurrence as it happened hundreds and hundreds of times over and over again throughout history. The point is, ". . . Title to the exercise of the royal power [or any other kind of sovereignty] arises only by prescription." (Edwin Robert Anderson Seligman and Alvin Saunders Johnson, Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, vol. 14, 1957, p. 429) 99% of all countries hold their titles to sovereign majesty over their nations originally ". . . by a successful employment of force [that is, by violence], confirmed by time, [long] usage, [and then by] prescription. . . ." (John Randolph, American Politics, Thomas Valentine Cooper and Hector T. Fenton, eds., Book III, 1892, p. 20) Literally hundreds of monarchs were deposed or dispossessed through these principles. And no court declared the right of the new nations. "Prescription" as a "juridical act" gives legitimacy without formal or official decree from a court or tribunal.

". . . There can be no doubt that prescription has conferred title [sovereignty] to the European discovers and their successor states over the hundreds of years that they have controlled the New World." (Thomas Flanagan, First Nations? Second Thoughts, 2000, p. 61) The deposed hereditary Aztec and Inca kings and emperors lasted dynastically for many many years after being conquered, but eventually lost all their sovereignty by acquiescence, submission or giving in when they could have continued their claims and maintained their rights even to this present day. This same scenario took place all over the world hundreds and thousands of times as monarchs were deposed by usurpers and failed to maintain or keep their claims alive.

they have controlled the New World." (Thomas Flanagan, First Nations? Second Thoughts, 2000, p. 61) The deposed hereditary Aztec and Inca kings and emperors lasted dynastically for many many years after being conquered, but eventually lost all their sovereignty by acquiescence, submission or giving in when they could have continued their claims and maintained their rights even to this present day. This same scenario took place all over the world hundreds and thousands of times as monarchs were deposed by usurpers and failed to maintain or keep their claims alive.

All a royal house needs to do to lose their rights on a permanent basis is to abandon them through acquiescence or neglect; that is, by a failure to protest or use their titles and arms in every generation for a hundred years. See number seven (#7) in Part I on how to maintain royal and sovereign rights, "How does a royal family maintain their rights? What is required? What is the proper protest that is acceptable and protective?"

(d) I read that nothing is official before a verdict from a competent court is achieved.

(d) I read that nothing is official before a verdict from a competent court is achieved.

This might be true in domestic law, but not in international law. There were "no tribunals" for international "prescription" for at least 300 years since "prescription" was re-established in the 1600's. (William Edward Hall, International Law, part II, chapter 2, number 36, 1880, p. 100) For thousands of years, "prescription" operated outside of any kind of court decree or verdict for thousands of years. One of the major founding fathers of international law declared during the time that no international court existed. He wrote:

. . . Every proprietor who for a long time and without any just reason neglects his right, should be presumed to have entirely renounced and abandoned it. This is what forms the absolute presumption (juris et de jure) of its abandonment. . . . (Emer de Vattel, The Law of Nations, Book II, chapter 11, no. 141)

"Juris et de jure" means by definition, "conclusive presumptions of law which cannot be rebutted by evidence." (www.lectlaw.com/def/j050.htm)

Emer de Vattel expressed it this way, ". . . immemorial prescription admits of no exception: both are founded on a presumption which the law of nature [not a court] directs us to receive as an incontestable truth [truth that cannot be impeached]." (The Law of Nations, Book II, #143)

In other words, in the day and time when there were no competent courts with proper jurisdiction, powerful "prescriptive" presumptions were legally binding and could not be altered. This is true today as well, because ". . . there is no requirement [in international law] to refer a dispute to international tribunals or other settlement mechanisms." (Jessup worldwide Competition for International Law, "Bench Memorandum 2010," p. 12)

In other words, dynasts can and did lose the royal prerogative outside of any court decree or verdict. Note the 12/19/2010 answer of Professor of International Law Noel Cox. He was asked about the loss of dynastic sovereignty. He wrote, ". . . Dynastic rights of a Sovereign may potentially end without a court ruling." As a declarative statement on this subject to make it clear and unmistakable, he wrote, "Legal rights can expire without the intervention of a court." (http://en.allexperts.com/q/Anglicans-943/2010/12/Dynastic-Law-1.htm) This is, of course, merely a confirmation of what is a well-known fact. "Prescription" does not require court involvement. This practice is especially true for all cases before about 1900 when international arbitration first began and no competent tribunals existed. "Prescription" was recognized and has operated in world events for centuries and thousands of years. No tribunal decree or verdict was needed for them to forfeit their sovereignty and royal rights. (See the answer to question number fourteen (#14) in Part I for more legal details and specific examples on this very important question, "Is court or arbitration necessary to effect the loss of sovereign rights for a deposed monarch?")

this subject to make it clear and unmistakable, he wrote, "Legal rights can expire without the intervention of a court." (http://en.allexperts.com/q/Anglicans-943/2010/12/Dynastic-Law-1.htm) This is, of course, merely a confirmation of what is a well-known fact. "Prescription" does not require court involvement. This practice is especially true for all cases before about 1900 when international arbitration first began and no competent tribunals existed. "Prescription" was recognized and has operated in world events for centuries and thousands of years. No tribunal decree or verdict was needed for them to forfeit their sovereignty and royal rights. (See the answer to question number fourteen (#14) in Part I for more legal details and specific examples on this very important question, "Is court or arbitration necessary to effect the loss of sovereign rights for a deposed monarch?")

(e) I read that a dynasty never loses its rights ever no matter what.

(e) I read that a dynasty never loses its rights ever no matter what.

Please read the answer number six (#6) in Part I, which is "Dynasty never forfeits its rights. Those rights cannot be forfeited. The principle of 'juris sanguinis' (right of blood) operates here. Is this true, or is it only partly true?" and answer number thirty-two (#33), which is, "The statement has been made that, 'In all the history of mankind, no deposed monarch has ever lost his rights except through debellatio.' What about it?" in Part II of "Sovereignty: Questions and Answers." The short answer is dynastic sovereignty can be lost and, if it is, it is permanent and final. The rules of "prescription" control this destiny.

Sadly, some only tell half the story. They quote how dynastic sovereignty cannot be forfeited, but fail to tell the whole complete truth about how it must be maintained or it will be lost irretrievably. That is, they fail to discuss the immense power of dynastic "prescription" as it relates to deposed monarchs and their successors. (See "Question #q" below.) When asked about the idea that a dynasty can never lose its rights no matter what, Noel Cox declared:

Sadly, some only tell half the story. They quote how dynastic sovereignty cannot be forfeited, but fail to tell the whole complete truth about how it must be maintained or it will be lost irretrievably. That is, they fail to discuss the immense power of dynastic "prescription" as it relates to deposed monarchs and their successors. (See "Question #q" below.) When asked about the idea that a dynasty can never lose its rights no matter what, Noel Cox declared:

There is a principle that the legal rights of a Sovereign are not automatically lost if they are deposed – equally, that the rights of a Government in exile may persist for some time after a revolution, invasion etc. However, it is also true that legal rights, unless exercised or acknowledged by others, do die out. I would suggest that after a few generations the rights of exiled Sovereigns could well be deemed to have ended. . . . (Letter 5/3/2011)

The rules and principles of prescription are extremely clear. Rights can be maintained forever or permanently and irrecoverably lost. This is a certainty as expressed by Emer de Vattel, ". . . immemorial prescription admits of no exception: both are founded on a presumption which the law of nature [not a court] directs us to receive as an incontestable truth [truth that cannot be impeached]." (The Law of Nations, Book II, #143)

(f) What about "res judicata," it cannot be applied outside a court decree.

(f) What about "res judicata," it cannot be applied outside a court decree.

"Prescription" has nothing to do with "res judicata" unless the case goes through a court. Keep in mind that deposed monarchs and legitimate governments-in-exile are excluded from all international courts as pertaining to the principle of sovereignty. Hence, the legal principle of "res judicata" is immaterial and irrelevant to the deposed royal, imperial or the princely right to rule.

What does have a powerful impact are "juridical acts" or legal presumptions made outside of court, which are binding and cannot be annulled, set aside or overturned outside a competent court. In other words, if a deposed monarch, or his successors, fails to protest or use their titles and arms in every generation, they permanently and irretrievably forfeit their sovereignty and royal claims. This is because, "immemorial prescription cuts off [bars or destroys] all claims." (Adam Smith, The Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith (1981-1987), vol. 5, Lectures on Jurisprudence, R. L. Meek, D. D. Raphael and P. G. Stein, eds., 2004, p. 72) And that is the end of it.

The only way this could be changed is if the usurping government by their sovereign domestic powers reinstated the once royal house --- the family, who are now commoners, could be restored. In other words, international law can lawfully take all internal sovereign and royal rights away from a deposed royal house by virtue of their negligence or "juridical" abandonment by extinctive "prescription," but only domestic sovereignty could give it back to them.

(g) Confusion is created because there is a difference between "Sovereign Dynastic Title" to sovereignty and "Territorial Sovereign Title." Territorial "prescription" cannot be applied to kings and monarchs.

(g) Confusion is created because there is a difference between "Sovereign Dynastic Title" to sovereignty and "Territorial Sovereign Title." Territorial "prescription" cannot be applied to kings and monarchs.

Territorial sovereignty is defined as the supreme internal ruling power within a territory. Interestingly the definition for internal sovereignty is identical to the definition for territorial sovereignty making the two inseparable. (See number fifteen (#15) in Part I, "I've heard that even scholars get the internal and external dimensions of sovereignty confused?") (See also "Question #o" below entitled, "The author believes that "prescription" involves external sovereignty and therefore it could not impact the internal sovereignty rights of deposed kings and sovereign princes."

"'Dynastic' or monarchical 'territorial' sovereignty" is a real and genuine reality. But so is republican territorial sovereignty. (Paul W. Schroeder, Reviewed work(s): "National Collective Identity: Social Constructs and International Systems by Rodney Bruce Hall," The International History Review, vol. 22, no. 1, March 2000, p. 145)

The conceptual error in the statement above about "Sovereign Dynastic Title" and "Territorial Sovereign Title" is that, "There is no essential difference between the sovereignty of the king and the sovereignty of the people." (Robert G. Haverton-Kelly, "The King and the Crowd," Contagion 3, 1996, p. 68) Trying to make a difference when there is no basic difference is problematic. It muddies the water. "The principle of monarchical [dynastic] sovereignty and the principle of popular sovereignty are really only . . . differences in the form of government." (Sources of Japanese Tradition, vol. 2: part 2: 1868 to 2000, Carol Gluck and Arthur E. Tiedemann, compilers, p. 162) "A traditional republic legitimately established under the natural law has the same moral and legal right to de jure sovereignty as that possessed by a sovereign royal house. . . ." (Stephen P. Kerr, "Theoretical Basis for and Functions of Non-Territorial and De jure Sovereignty under International Law," Master's Thesis, George Washington School of Law, 1977, p. 103) Why? --- because, "Dynastic sovereignty" is nothing more or less than "sovereignty vested in a monarch and the monarch's heirs." (Richard W. Mansbach, Kirsten L. Rafferty, Introduction to Global Politics, 2008, p. 66) By the same token, Repulican sovereignty is nothing more or less than soverignty vested in a Republic. There is no basic difference.

there is no basic difference is problematic. It muddies the water. "The principle of monarchical [dynastic] sovereignty and the principle of popular sovereignty are really only . . . differences in the form of government." (Sources of Japanese Tradition, vol. 2: part 2: 1868 to 2000, Carol Gluck and Arthur E. Tiedemann, compilers, p. 162) "A traditional republic legitimately established under the natural law has the same moral and legal right to de jure sovereignty as that possessed by a sovereign royal house. . . ." (Stephen P. Kerr, "Theoretical Basis for and Functions of Non-Territorial and De jure Sovereignty under International Law," Master's Thesis, George Washington School of Law, 1977, p. 103) Why? --- because, "Dynastic sovereignty" is nothing more or less than "sovereignty vested in a monarch and the monarch's heirs." (Richard W. Mansbach, Kirsten L. Rafferty, Introduction to Global Politics, 2008, p. 66) By the same token, Repulican sovereignty is nothing more or less than soverignty vested in a Republic. There is no basic difference.

Dynastic sovereignty, republican sovereignty and territorial sovereignty are distinctions without a primary or fundamental variation. Why? Because, "There are not different kinds of sovereignty. A sovereign . . . is not a particular form . . . such as a monarchy or republic or democracy. . . . Their ruling authority will have the same basic characteristics. . . ." (Robert Jackson, Sovereignty: Evolution of an Idea, 1988, pp. 10-11) Thomas Hobbes declared that ". . . the power of sovereignty is the same in whomsoever it be placed" whether a king or a republican president and legislature. ("Readings from the Leviathan," Readings in Potential Philosophy, Francis Coker, ed., 1914, p. 326) In other words, the same principles apply to all. This was emphasized in the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia and in the writings of the founding fathers of international law, who saw no basic or seminal difference between them.

In terms of "prescription," the rules are the same for a kingdom or principality as they are for any of the other kinds of ousted governments. In other words, ". . . In a hereditary monarchy, the right to rule remains with the royal descendant until he has lost it through the long process of prescription." (John A. Ryan, "Catholic Doctrine on the Right of Self-Government," Catholic World, vol. 108, January 1919, p. 444) Dynastic sovereignty, just like territorial sovereignty, which is internal sovereignty, is permanently lost by "prescription." Samuel Pufendorf (1632-1694), another one of the founding fathers of international law, confirms this important truth. In a chapter entitled, "Of the Way of Acquiring Sovereignty especially Monarchical," it states that "prescription" is one of the ways of losing dynastic sovereignty to a usurper, it declares that, ". . . the rightful Prince shall labor to reduce the Rebels to Obedience or at least by solemn declaration shall protest and preserve his right over them; till by long Acquiescence and silence he may be presumed to have given up his claim [which is legal abandonment or an irretrievable loss of royal and sovereign rights]." (Of the Law of Nature and Nations, Jean Barbeyrac and William Percivale trans., Book VII, chapter 7, no. 5, p. 577)

In terms of "prescription," the rules are the same for a kingdom or principality as they are for any of the other kinds of ousted governments. In other words, ". . . In a hereditary monarchy, the right to rule remains with the royal descendant until he has lost it through the long process of prescription." (John A. Ryan, "Catholic Doctrine on the Right of Self-Government," Catholic World, vol. 108, January 1919, p. 444) Dynastic sovereignty, just like territorial sovereignty, which is internal sovereignty, is permanently lost by "prescription." Samuel Pufendorf (1632-1694), another one of the founding fathers of international law, confirms this important truth. In a chapter entitled, "Of the Way of Acquiring Sovereignty especially Monarchical," it states that "prescription" is one of the ways of losing dynastic sovereignty to a usurper, it declares that, ". . . the rightful Prince shall labor to reduce the Rebels to Obedience or at least by solemn declaration shall protest and preserve his right over them; till by long Acquiescence and silence he may be presumed to have given up his claim [which is legal abandonment or an irretrievable loss of royal and sovereign rights]." (Of the Law of Nature and Nations, Jean Barbeyrac and William Percivale trans., Book VII, chapter 7, no. 5, p. 577)

Or, on the other hand, dynastic sovereignty can be preserved endlessly and forever, if the claim is kept alive in the way specified by law. The point is, in terms of "prescription" and sovereignty:

. . . there is not strictly, in human nature, any such thing as an absolutely indefeasible right [that is, by definition, something incapable of being annulled or rendered void]. Sovereign right itself furnishes no exception to this general principle. (Edward Smedley and Hugh James Rose, Encyclopaedia Metropolitana; or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, vol. 2, 1845, p. 714)

In other words, "[Sovereignty] is conferred by law. . . ." (Neil MacCormick, Questioning Sovereignty: Law, State, and Nation in the European Commonwealth, 1999, p. 127) It can also be destroyed by law. The juridical rules of "prescription" are a part of those laws which can totally destroy internal and external sovereignty.

It is as Sir William Blackstone, the great jurist wrote, ". . . the law maketh the king." (Commentaries on the Laws of England, 1922, p. 213) Again, "Sovereignty is . . . merely [a] legal conception. . . ." (Neil MacCormick, Questioning Sovereignty: Law, State, and Nation in the European Commonwealth, 1999, p. 127) Certainly, it is time honored, and doubtlessly the most precious and important of all governmental rights, but it can be permanently lost to a once "de jure" deposed monarch and his successors. That is, after a hundred years or immemorial "prescription," it is irreparably broken into dust or permanently torn apart:

To object that sovereign rights will thus be arbitrarily destroyed [ruined or lost] is an unwarranted assumption, since those rights cannot reasonably be shown to exist [any longer]. (Harvard Law Review Association, Harvard Law School, Harvard Law Review, vol. 17, 1904, pp. 346-347) (See (#33) in Part II)

"Prescription" has eliminated the rights of deposed monarchs for centuries. There are hundreds of historical examples all over the world (about 400 in the 19th and 20th centuries) as nations illegally cast aside their rightful monarchs and became republics or democracies or replaced dethroned tyrants and legitimate monarchs. Most are lost to history and immemorial "prescription," because of binding legal or "juridical" abandonment wherein all internal rights and privileges devolve to the usurpers who have governed for a long period of time. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abolished_monarchy)

Please see ("Question #q") below on this page. It is entitled: "Are there any statements that directly links deposed dynasties, the loss of royal privileges, and 'prescription?'"

(h) I read that deposed royal houses can keep their rights forever.

(h) I read that deposed royal houses can keep their rights forever.

See answer number seven (#7) in Part I entitled, "How does a royal family maintain their rights? What is required? What is the proper protest that is acceptable and protective?" Most of the answers on both Part I and Part II reiterate the same principle. As Dr. Oldys declared in a legal battle, ". . . the late king, being once a king, had, by the Law of Nations . . . tho’ he had lost his kingdoms . . . still retained a right to the privileges that belong to Sovereign Princes." (Sir Robert Phillimore, Commentaries upon International Law, vol. 1, no. 256, chapter 13, p. 433) This, of course, no longer includes the command of armies, etc., but all the rights are still intact even though they are mostly dormant; that is, the power to exercise most of those rights are gone. Such a prince, and his legitimate successors, can, however, honor and be honored and make laws as any government in exile can do as long as their rights are legally preserved. It is important to know how rights are both legally terminated and how they can be preserved and kept alive forever. The whole future of nobility and royalty depends on this important legal knowledge. We attempt to answer questions to ensure that people understand these principles.

(i) "Prescription" according to one judge is not relevant as an international legal principle, or at least it is extremely or excessively doubted according to an internet writer.

(i) "Prescription" according to one judge is not relevant as an international legal principle, or at least it is extremely or excessively doubted according to an internet writer.

The core principles of "prescription" have always been considered to be a just and important. On this subject, it should ". . . be borne steadily in mind . . . [that it is] in the highest degree irrational to deny that prescription is a legitimate means of International Acquisition. . . ." (Sir Robert Phillimore, Commentaries upon International Law, vol. 1, no. 256, chapter 13, p. 300) From the first attempt to codify international law in 1795 under ". . . General Principles of the Law of Nations," we read, "(11) Possession from time immemorial creates among nations the right to prescription." (Edmund Jan Osmañczyk, Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: G to M, Third ed., vol. 2, Anthony Mango, ed., "Law of Nations, Gregoire's Principles, 1795," 2003, p. 1280) The International Law Commission upholds "prescription" as part of the most important rules of International law. They wrote in one of their reports that:

highest degree irrational to deny that prescription is a legitimate means of International Acquisition. . . ." (Sir Robert Phillimore, Commentaries upon International Law, vol. 1, no. 256, chapter 13, p. 300) From the first attempt to codify international law in 1795 under ". . . General Principles of the Law of Nations," we read, "(11) Possession from time immemorial creates among nations the right to prescription." (Edmund Jan Osmañczyk, Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: G to M, Third ed., vol. 2, Anthony Mango, ed., "Law of Nations, Gregoire's Principles, 1795," 2003, p. 1280) The International Law Commission upholds "prescription" as part of the most important rules of International law. They wrote in one of their reports that:

The salient aspect of this part of international law lies in the rules relating to the original acquisition of territorial sovereignty by discovery, occupation, conquest and prescription. Rights and claims . . . [that] have been traditionally regarded as synonymous with the most vital interest of States. . . ." (Survey of International Law 1949, Chapter III: Jurisdiction of States, (5) The Territorial Domain of States, No. 64, pp. 38-39)

In international law, "prescription" is considered to be among the highest and most important of all laws, because it is part of the law of nature. The lessor law is called the "voluntary law," which is gleaned from customs and is called "temperamentum," because it is ". . . shifting and changeable with the changing manners, fashions, creeds, and customs [of people]." (Sheldon Amos, The Science of Law, The International Scientific Series, vol. 10, 1885, p. 341) The other is the essential, fundamental moral principles called the "laws of nature," which never change and are called "summum jus." (Ibid.) Sir William Blackstone, the renown English jurist, declared the following about this greater law, which is part of the law of nations. He explained that the:

. . . law of nature [the higher law], being co-equal with mankind and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original. ("Of The Nature of Laws in General" 2009: http://libertariannation.org/a/f21l3.html)

. . . law of nature [the higher law], being co-equal with mankind and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original. ("Of The Nature of Laws in General" 2009: http://libertariannation.org/a/f21l3.html)

Hugo Grotius, considered to be the father of international law, was "persuaded that nations, or sovereign powers, are subject to the authority of the law of nature . . . [he calls this law which even sovereignty must comply with] the internal law of nations. . . ." (Emer de Vattel, Preface to his book The Law of Nations, 1758: http://www.constitution.org/vattel/vattel-01.htm) He made it clear that ". . . Prescription doth truly belong to the Law of Nature. . . ." (Samuel Pufendorf, Of the Law of Nature and Nations, Book IV, chapter 12, no. 8, p. 357) "Sovereignty [of course] is essentially an internal concept, the locus of ultimate authority in a society. Its origins are in 'sovereign princes. . . .'" (Louise Henkin, "The Mythology of Sovereignty," Essays in Honour of Wang Tieya, Ronald St. J. Macdonald, ed., 1994, p. 352) As such both sovereignty and dynasties are subject to the law of nature. Jean Boden (1530-1596), one of the great champions of sovereignty, made it clear that ". . . kings were subject to the law of nature," and thus to the rules of "prescription" as well, because they are a part of the highest laws known to man. (On Sovereignty: Four Chapters from the Six Books of the Commonwealth, Julian H. Frnaklin, ed., 2004, p. xxiv) The point is:

H. Frnaklin, ed., 2004, p. xxiv) The point is:

The laws of nature . . . emanate from a higher authority than any human government. They are written upon the hearts of all men; exist before governments are organized . . . "and are binding all over the globe, in all countries and at all times." Adams v. Peo., 1 N. Y. 173, 175. (William Mack and William Benjamin Hale, Corpus Juris, "Allegiance," note 41[e], 1915, p. 1150)

"Prescription" is part of the "Internal Law of Nations," which is involved with internal sovereignty --- the sovereignty of royal houses and legitimate governments in exile. It is part of the "Arbitrary Laws of Nature." (op.cit., Vattel) That is, ". . . By the law of nations, prescription, when of so long standing, has been always allowed to give a right. And this the public peace and tranquility of the whole world makes necessary; which general peace and wealth of the community is the great end of society and government. . . ." (Alban Butler, The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints, vol. 4, note, 2006, p. 417) "Prescription" is universally accepted in every civilized nation and is binding on royal as well as republican sovereignty. See the answer to number twenty-two (#22). The answer is very pertinent, it is, "Some scholars have denied "prescription" in international law. If so, how can you promote it as something of such great importance to nobility and royalty?" in Part II.

(j) "Prescription" does not "operate in cases where possession was maintained by force."

(j) "Prescription" does not "operate in cases where possession was maintained by force."

This is a true principle. But be sure you do not confuse belligerent occupation with "prescription." They are two different things. See the answer to number twenty-eight (#28) in Part II of "Sovereignty: Questions and Answers" entitled, "After belligerent occupation ends and the new regime takes over, it is a well-known fact that "de jure" sovereign recognition is generally given to the usurping or newly formed government. In that case, how can a legitimate government in exile or exiled monarch still rightfully claim sovereignty?"

This is a true principle. But be sure you do not confuse belligerent occupation with "prescription." They are two different things. See the answer to number twenty-eight (#28) in Part II of "Sovereignty: Questions and Answers" entitled, "After belligerent occupation ends and the new regime takes over, it is a well-known fact that "de jure" sovereign recognition is generally given to the usurping or newly formed government. In that case, how can a legitimate government in exile or exiled monarch still rightfully claim sovereignty?"

(k) "Prescription" according to this article I read cannot transfer sovereignty if the original occupation by the usurper was by force.

(k) "Prescription" according to this article I read cannot transfer sovereignty if the original occupation by the usurper was by force.

This is merely a confusion between domestic and international "prescription." International "prescription" rectifies violent usupations of sovereignty after 100 years of undisputed rule. In other words, ". . . [international] prescription . . . mellows into legality governments that were violent in their commencement." (William Edward Hartpole Lecky, The French Revolution: chapters from the author's History of England during, 1904, p. 215) To clarify this further please see the answer for question number twenty-six (#26) in Part II of "Sovereignty: Questions and Answers." The question is, "How does civil "prescription" differ from international "prescription?" Are there some important differences?" The differences are profound and very important.

(l) In addition, the author says that "prescription" cannot take place unless the reign of the usurper is "peaceful." Which he interprets to mean serene and without any conflicts.

(l) In addition, the author says that "prescription" cannot take place unless the reign of the usurper is "peaceful." Which he interprets to mean serene and without any conflicts.

No, this interpretation is wrong. "Peaceful [means] acquiescence by any state that has any title." (Jessup worldwide Competition for International Law, "Bench Memorandum 2010," p. 12) Disturbance by anyone else is immaterial. The following paragraph is from the answer to question number twenty-four (#24) in Part II.

". . . Peaceful possession is finding that the dispossessed state has acquiesced [abandoned overtly or by implication discarded] the possession." (Ibid.) In other words, "This meant that the possession had to go unchallenged." (Randall Lesaffer, "Argument from Roman Law in Current International Law: Occupation and Acquisitive Prescription," The European Journal of International Law, vol. 16, no. 1, 2005, p. 50) The original holder of sovereignty, or his successors, must not challenge the usurper's right to rule. They must neglect their rights in silence till legal abandonment occurs, which in immemorial "prescription" takes 100 years. In other words, ". . . There cannot be peaceful possession unless there is an absence of objection [by the deposed monarch or government in exile]." (John O'Brien, International Law, 2001, p. 211) War, or lack of peaceful rule, does not stop "prescription." Peaceful does not refer to tranquility of rule, or a rule without problems, but to a lack of protest from the deposed former government. ". . . Acquiescence . . . is a precondition of that possession being peaceful. . . ." (D. P. O'Connell, International Law, 2nd. ed., 1970, p. 110) "'Peaceable' thus meant acquiescence [implied consent and abandonment] by the opposing party." (Randall Lesaffer, "Argument from Roman Law in Current International Law: Occupation and Acquisitive Prescription," The European Journal of International Law, vol. 16, no. 1, 2005, p. 51) One of the essential requirements for "prescription" to succeed is that there must be acquiescence, silence, implied consent or a lack of protest from the former sovereign or government in exile. That is what "peaceful" means, that is, the original king, sovereign prince or government in exile does not contest or dispute the usurper's "defacto" rule. So, "what conduct is sufficient to prevent possession from being peaceful and uninterrupted? Any conduct indicating a lack of acquiescence, e.g. protest. Effective protests prevent acquisition of title by prescription." (Alina Kaczorowska, Public International Law, 4th ed., 2010, p. 281) It could hardly be more clear.

2005, p. 51) One of the essential requirements for "prescription" to succeed is that there must be acquiescence, silence, implied consent or a lack of protest from the former sovereign or government in exile. That is what "peaceful" means, that is, the original king, sovereign prince or government in exile does not contest or dispute the usurper's "defacto" rule. So, "what conduct is sufficient to prevent possession from being peaceful and uninterrupted? Any conduct indicating a lack of acquiescence, e.g. protest. Effective protests prevent acquisition of title by prescription." (Alina Kaczorowska, Public International Law, 4th ed., 2010, p. 281) It could hardly be more clear.

However, because some misinterpret "peaceful" to mean without any kind of conflict, many jurists and international scholars have not and do not use this word. Instead they write similar to the following citations, "Long continued and undisputed possession is accepted as conferring a sound international title by prescription. . . ." (Thomas Alfred Walker, A Manual of Public International Law, Part II, no. 13, 1895, p. 34) Or, "continuous and undisturbed exercise of sovereignty," by the usurper. (Lassa Francis Lawrence Oppenheim, International Law, a Treatise, vol. 1, Ronald F. Roxburgh, ed., 1920, pp. 401-402) Again, "Peaceful" means undisturbed or undisputed:

The great preponderance of opinion is to the effect that long undisturbed possession by a sovereign of a particular piece of territory gives him a strong prima facie claim to such. . . . 'The general consent of mankind,' says Mr. Wheaton, 'has established the principle that long and uninterrupted possession by one nation excludes the claim of every other.'" (Francis Wharton, Commentaries on Law, chapter 4, no. 153, 1884, pp. 231-232)

Misinterpretations obviously do not promote accuracy. They encourage false beliefs. Our efforts are focused on providing clear and solid answers that empower people to see things as they really are. This is not always easy, but it is our endeavor nonetheless. Explaining things and providing proof, however, is worth it to us, because true "knowledge is power." We will do our best to provide the facts and evidence needed to promote the ideals of nobility and protect the public from errors. "Truth is a Treasure." (See "The Standard for All that We Do")

(m) The author brings up the excuses of fear and/or ignorance saying that such prevents "prescription" from destroying rights.

(m) The author brings up the excuses of fear and/or ignorance saying that such prevents "prescription" from destroying rights.

These problems must be dealt with before 100 years expires in immemorial "prescription." For example, acquiencence, the lack of protest, neglect or implied abandonment is essential for prescription to work. "Acquiescence occurs in circumstances where a protest is called for and does not happen," but it also means that the protest "does not happen in time in the circumstances. Essentially [it was] on this basis that Huber found in favour of the Netherlands in the Island of Palmas Case." That is, a protest can be given too late to count. Evidence of duress, etc. must be given before the final deadline of 100 years, or the various valid justifications become inadmissible or irreversibly precluded from consideration. They simply cannot be admitted after the "prescriptive" transfer of internal sovereignty becomes conclusive and final.

(See the answer to question number twenty-four (#24) in Part II, which is, "Are there no exceptions to the loss of de jure internal sovereignty through "prescription?" to see how various justifications are invalid or must be dealt with early on. Also see the answers to (#14) in Part I and (#33) in Part II)

(n) It was declared that no deposed heir apparent can lose his rights except by a voluntary formalized or official act.

(n) It was declared that no deposed heir apparent can lose his rights except by a voluntary formalized or official act.

Actually, "prescription" works without a formalized or official act. Note the following:

. . . a state may acquire territory, without formal annexation, by means of prescription, or uncontested occupation of territory of another state over a long period of time. . . . (The Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 1, "Annexation," 1985, p. 10)

What is significant here is a usurper may acquire territory "without formal annexation," that is, without an official takeover or formal legal act of establishment. If it is formal, it is legalized by court or treaty. If not, it is informal, which means there is no court, treaty or legal document involved. The point is, loss of rights is usually never completed by a formal proclamation.

Again, hundreds of royal houses completely lost all their royal and sovereign rights to revolutions and/or illegal referendums all over the earth, because they never protested or continued to use their titles and arms. After 100 years, the highest legal presumption on earth "juris et de jure" takes effect making the loss permanent, conclusive and irreversible. In over 90% of these situations "without formal annexation," the new republican governments obtained the only thing that these monarchs had left, that is, internal, "de jure," nonterritorial sovereignty. This loss is set in legal cement and cannot be undone, because it is like sure and solid legally as granite rock.

irreversible. In over 90% of these situations "without formal annexation," the new republican governments obtained the only thing that these monarchs had left, that is, internal, "de jure," nonterritorial sovereignty. This loss is set in legal cement and cannot be undone, because it is like sure and solid legally as granite rock.

(o) The author believes that "prescription" involves external sovereignty and therefore it could not impact the internal sovereignty rights of deposed kings and sovereign princes.

(o) The author believes that "prescription" involves external sovereignty and therefore it could not impact the internal sovereignty rights of deposed kings and sovereign princes.

This assertion contradicts all the facts known about "prescription." To understand this clearly go to the answer to number fifteen (#15) in Part I entitled, "I've heard that even scholars get the internal and external dimensions of sovereignty confused?" The answer to this question is definitive. However, various other answers also elaborate on this important understanding. See also, number twenty-four (#24) in Part II, "Sometimes it is confusing to understand all the ins and outs of "prescription" and the law. What are the basics of recognition, international tribunals, and their relationship to deposed monarchs? Please clarify."

Briefly the fact that "prescription" is legally binding on internal sovereignty can easily be distinguished by understanding what territorial sovereignty is, and then noting that territorrial sovereignty is subject or answerable to the rules of "prescription." Note the following defintion, "Territorial sovereignty was described in the Isle of Palmas Arbitration (The Netherlands v US) as being the 'right to exercise therein (i.e. on the territory) . . . the functions of a sovereign.'" (Alina Kaczorowska, Public International Law, 4th edition, 2010, p. 265) Internal sovereignty is identical in meaning, it is also "the right to exercise therein (i.e. on the territory . . . the functions of a sovereign." In other words, internal sovereignty and territorial sovereignty have one and the same definition. Internal sovereignty is defined as the right ". . . to exercise supreme authority over all persons and things within its territory, [in other words] sovereignty is territorial supremacy [which is another word for territorial sovereignty]." (Lassa Oppenheim, International Law: a Treatise, vol. 1, 1905, p. 171) These two concepts (internal and territorial sovereignty) have identical meanings. In fact, because they are synonyms and are interchangeable, "territorial sovereignty or internal sovereignty" can be used together because they mean the same thing. (Rodrigo A. Gómez S., "Rapanui and Chile, a debate on self-determination," Master’s Thesis for Victoria University of Wellington, 2010, p. 31) "Territorial sovereignty. . . [is] 'an aspect of sovereignty connoting the internal, rather than the external, manifestation of the principle of sovereignty.'" (Wang Tieya, "International Law in China," Recueil Des Cours, vol. 2, 1990, p. 297) (Clive Parry and John P. Grant, Encyclopaedic Dictionary of International Law, 1986, p. 360)

"Territorial sovereignty was described in the Isle of Palmas Arbitration (The Netherlands v US) as being the 'right to exercise therein (i.e. on the territory) . . . the functions of a sovereign.'" (Alina Kaczorowska, Public International Law, 4th edition, 2010, p. 265) Internal sovereignty is identical in meaning, it is also "the right to exercise therein (i.e. on the territory . . . the functions of a sovereign." In other words, internal sovereignty and territorial sovereignty have one and the same definition. Internal sovereignty is defined as the right ". . . to exercise supreme authority over all persons and things within its territory, [in other words] sovereignty is territorial supremacy [which is another word for territorial sovereignty]." (Lassa Oppenheim, International Law: a Treatise, vol. 1, 1905, p. 171) These two concepts (internal and territorial sovereignty) have identical meanings. In fact, because they are synonyms and are interchangeable, "territorial sovereignty or internal sovereignty" can be used together because they mean the same thing. (Rodrigo A. Gómez S., "Rapanui and Chile, a debate on self-determination," Master’s Thesis for Victoria University of Wellington, 2010, p. 31) "Territorial sovereignty. . . [is] 'an aspect of sovereignty connoting the internal, rather than the external, manifestation of the principle of sovereignty.'" (Wang Tieya, "International Law in China," Recueil Des Cours, vol. 2, 1990, p. 297) (Clive Parry and John P. Grant, Encyclopaedic Dictionary of International Law, 1986, p. 360)

Traditional international law allows states to acquire territorial sovereignty [which is internal sovereignty] through one of five different methods including "accretion," "occupation," "prescription," "conquest," and "cession." However, after World War II, the United Nations Charter prohibits the illegal use of force, thus forced cession and conquest are no longer valid methods of acquiring territorial [or internal] sovereignty for a state. (Zoe Keyuan, "South China Sea Studies in China: A legal Perspective," Southeast Asian Studies in China, Saw Swee-Hock and John Wong, eds., 2007, p. 174)

Now, note that "prescription" is legally binding on territorial sovereignty, which is the sovereignty of all "de jure," deposed royal houses and legitimate governments in exile. In fact, ". . . Dynastic sovereignty and territorial sovereignty [are] so closely intertwined and overlapping. . . ." that there is little difference between them. (Paul W. Schroeder, "Reviewed work(s): National Collective Identity: Social Constructs and International Systems by Rodney Bruce Hall," The International History Review, vol. 22, no. 1, March 2000, p. 145) In fact, they can be used together as in "territorial/dynastic sovereignty." (Victor Segesvary, World State, National States, or Non-Centralized Institutions, 2004, p. 19) In other words, deposed dynasties are vulnerable and subject to the provisions of "prescription." Why? Because internal sovereignty, also known as territorial sovereignty, is the sovereignty of deposed monarchs. In other words, deposed sovereignty is territorial or internal.

Under the chapter heading of "International Law of Territorial Sovereignty," it states, "There are several recognized modes of acquiring territorial sovereignty under international law." (Thomas J. Schoenbaum, Peace in Northeast Asia, chapter 3.3, no. 3.3.1, 2008, p. 30) "Prescription" is one of them. Again, by another international scholar, ". . . Territorial sovereigntly may be acquired by . . . prescription." (Lowell S. Gustafson, The Sovereignty dispute over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands, 1988, p. xi) Again, ". . . On questions of territorial sovereignty [which by definition is internal] . . . immemorial prescription is admitted . . . by the great majority of jurists. . . ." (John Westlake, International Law, part 1, 1910, p. 364) "Prescription," because it has authority over internal or territorial sovereignty, can and has both destroyed or preserved the sovereignty of deposed monarchs for hundreds and hundreds of princely and royal houses thoughout the centuries and for thousands of years.